ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

Must Listen Podcasts for English Teachers

If you’re new to the podcast world, let me give you a big, warm WELCOME! Podcasts have been a game-changer for me both for professional development and for adding new texture, voices, and perspectives to my Essential Question based units.

The curated list below is broken into these two categories: podcasts for PD and podcasts for content. Each of these will inspire you with new ideas and restore your joy and love of teaching at your core.

If you’re new to the podcast world, let me give you a big, warm WELCOME! Podcasts have been a game-changer for me both for professional development and for adding new texture, voices, and perspectives to my Essential Question based units.

The curated list below is broken into these two categories: podcasts for PD and podcasts for content. Each of these will inspire you with new ideas and restore your joy and love of teaching at your core.

PODCASTS FOR PD:

Looking for a community of teachers ready to break barriers and challenge the status quo? Join us at Brave New Teaching! Marie Morris of The Caffeinated Classroom and I adore hosting this podcast and helping teachers at every step of their journey.

These are two of our most downloaded episodes. Jump in and give them a listen!

There’s a reason Jenn Gonzalez’ podcast has over 8 million downloads — her content is challenging, brilliant, and honest. Start with this episode:

Join Amanda for a her expertise in all things Writing Workshop! As a middle school teacher for over a decade, Amanda will give you support AND ideas!

Betsy Potash just keeps churning out episode after episode full of strategies and inspirational ideas. I love this one about real-world research projects!

Looking for a teacher bestie down the hall that keeps it real? Pop in your earbuds and dial up The Educator’s Mindset!

PODCASTS FOR ELA CONTENT:

If there’s a dystopian unit in your future, it’s time you included LIMETOWN into the mix! This delightful 6-part podcast takes us through the fictional world of Limetown, a city of over 300 residents that vanished virtually overnight. No one really knows what was going on in this town (but we do know it was home to a mysterious research facility), and investigative journalist Lia Haddock is on the case. Follow along with Lia’s story as students watch their own dystopian worlds unfold in their novels. Grab my listening sketchnotes to help you through the podcast part and sit back and enjoy!

“Lore is an award-winning, critically-acclaimed podcast about true life scary stories. Lore exposes the darker side of history, exploring the creatures, people, and places of our wildest nightmares. Because sometimes the truth is more frightening than fiction. Each episode examines a new dark historical tale in a modern campfire experience.”

This episode pairs beautifully with The Crucible or the study of Margaret Atwood’s poem: “Half-Hanged Mary”. If superstition is on your theme list, give this one a listen!

With each episode of This American Life, Ira Glass looks into a slice of American life, typically through profiling a unique individual’s life. One of my favorites is “Switched at Birth”. I love to share this episode with students to talk about writing structure and tension.

This is a wonderful podcast to pair with any unit on memoir or writing — take a look through the huge list of favorite episodes here to get an idea of the huge variety of topics discussed on the podcast!

“What's CODE SWITCH? It's the fearless conversations about race that you've been waiting for. Hosted by journalists of color, our podcast tackles the subject of race with empathy and humor. We explore how race affects every part of society — from politics and pop culture to history, food and everything in between. This podcast makes all of us part of the conversation — because we're all part of the story. Code Switch was named Apple Podcasts' first-ever Show of the Year in 2020.”

Use this podcast to practice the important art of listening to other stories and experiences as we educate ourselves more deeply on the impact of race.

“Lauren Clark is a hair stylist in D.C. When a stranger sexually assaulted her in 2013, it sparked a years-long courtroom saga and a campaign for justice. Her story started The Post’s Amy Brittain on a reporting journey that has lasted for nearly three years — one that played out in the middle of a larger cultural reckoning.”

If you’re working on a unit examining the role of gender, this story gives powerful light to women who are all too often afraid to speak up and be labeled as attention seeking and not taken seriously.

“Each week of On Eyre, Vanessa and Lauren Sandler will take a critical look at the text and ask themselves ‘does this old book still have something to say in our world?’ But before we jump into the first chapter, a few questions need to be answered. Questions like: Who is Charlotte Bronte, and why should anyone (who isn't Vanessa) care about this book?”

This is the most intensive, analytical look at Jane Eyre I’ve ever found. The hosts break down the novel chapter by chapter and analyze through a lens of desire and power. This is a MUST listen for anyone who teaches the novel or is a huge, nerdy fan.

Calling all teachers of literary analysis — here is your podcast. Each season of Dissect tackles an album and analyzes each song one by one. From Beyonce to Mac Miller, the genres range widely and the analysis is pointed, clever, and enjoyable to listen to. Most recently was Season 9:

“Season 9 is dedicated to Mac Miller’s Swimming In Circles. Over 14 episodes, we dissect the music, lyrics, and meaning of Mac’s beautifully honest efforts to swim amidst the often tumultuous currents of the human experience.”

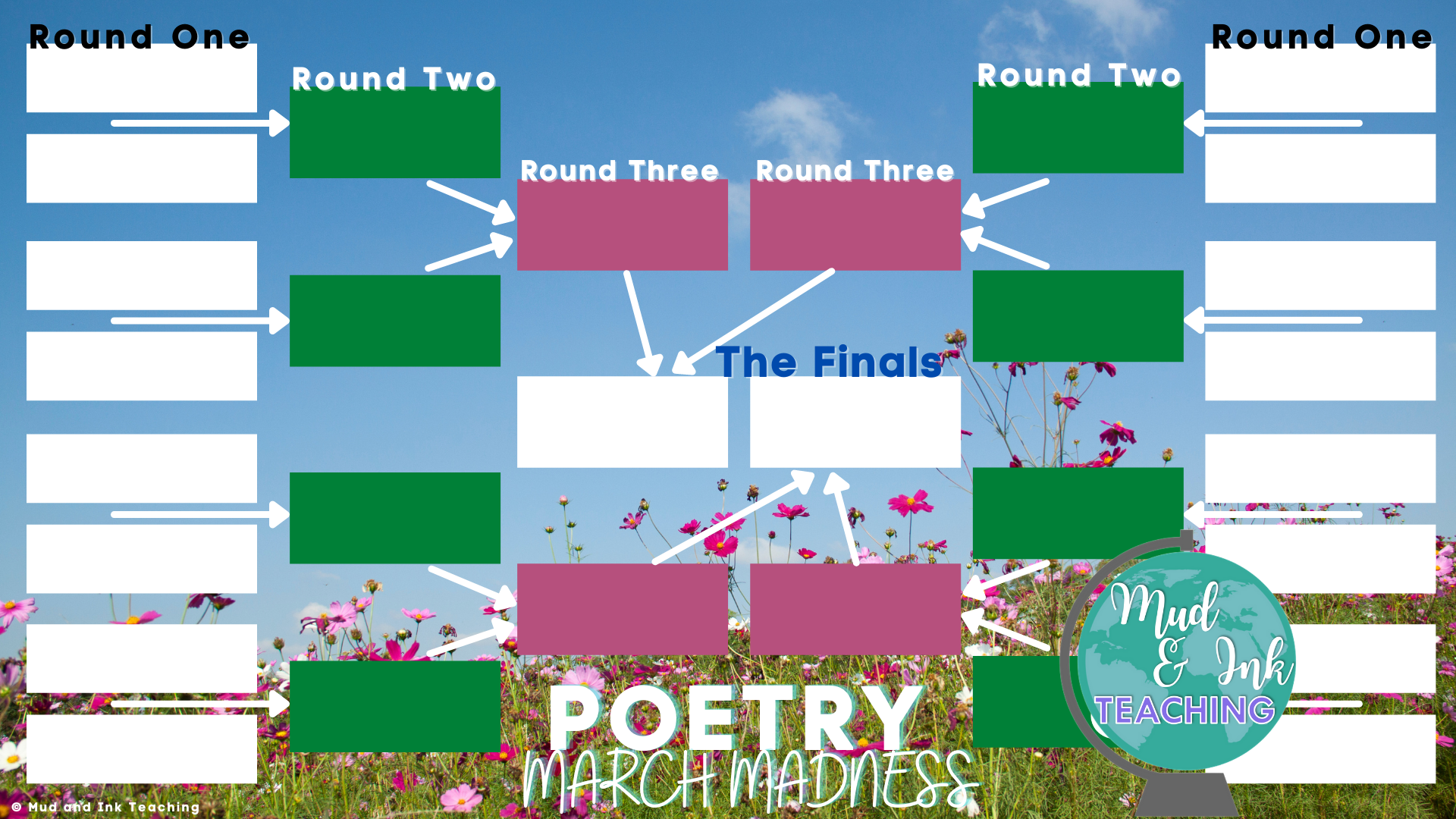

If you’re looking to broaden your own poetry arsenal or you’re working through an exclusive poetry unit, this Poem of the Day Podcast will give you and your students wonderful access to new poetry. This daily podcast has a wealth of episodes to scour through! The Poetry Foundation website has even more to explore, but this podcast just might get you back in the zone when it comes to poetry. If you’re looking to step up your poetry game in the classroom, here are 30 poems to get started with right away!

“What is it like to be famous before you’re famous? What is it like to walk in the shoes of another person? Each episode of Imagined Life takes you on an immersive journey into the life of a world-famous person. It’ll be someone you may think you know, even admire -- or maybe the opposite. You’ll get clues to your identity along the way. But only in the final moments will you find out who ‘you’ really are.” This podcast is fun to do similar to first chapter Friday or in the creative writing classroom.

“Hidden Brain explores the unconscious patterns that drive human behavior and questions that lie at the heart of our complex and changing world.”

I love using this episode when contemplating happiness and the American Dream while teaching The Great Gatsby. It gives us a great non-fiction, research-based look at happiness to apply as a lens.

If teaching the American Dream is on your to do list this year, Gangster Capitalism should also be on that list. This podcast digs into the SAT and college entrance scandals spearheaded by Rick Singer. Hear about how the wealthiest Americans work their way into college — in a much different way than those who are all working hard for it. Pair this podcast with my unit on The Great Gatsby for a rich discussion about wealth in America and how that impacts the American Dream.

Hosted by the brilliant Ada Limon, this podcast shares contextual thoughts related to a different poem each day. Episodes are rarely longer than seven minutes in length, making them easy to use in the classroom or as a starting place for homework. If you teach any YA novel that deals with the ways in which Black young men have been affected by police brutality, this poem is a beautiful pairing.

“Admissions Officers Hannah and Mark share the complex and dynamic work happening inside the Yale Office of Undergraduate Admissions. The podcast gives firsthand accounts of how officers read applications, make decisions within the Admissions Committee, and collaborate with other offices and resource centers. Yale College receives more than 35,000 applications annually for a first-year class of 1,550 students. Hannah and Mark give an inside look into the strategies and processes that enable admissions officers to attract promising applicants from around the world, consider every applicant through a whole-person review process, and build a class filled with strong students from an amazingly diverse collection of backgrounds. Recorded inside the Office of Undergraduate Admissions on Hillhouse Avenue, this new podcast pulls back the curtain to reveal some of Yale’s most fascinating and rewarding work.”

LET’S GO SHOPPING

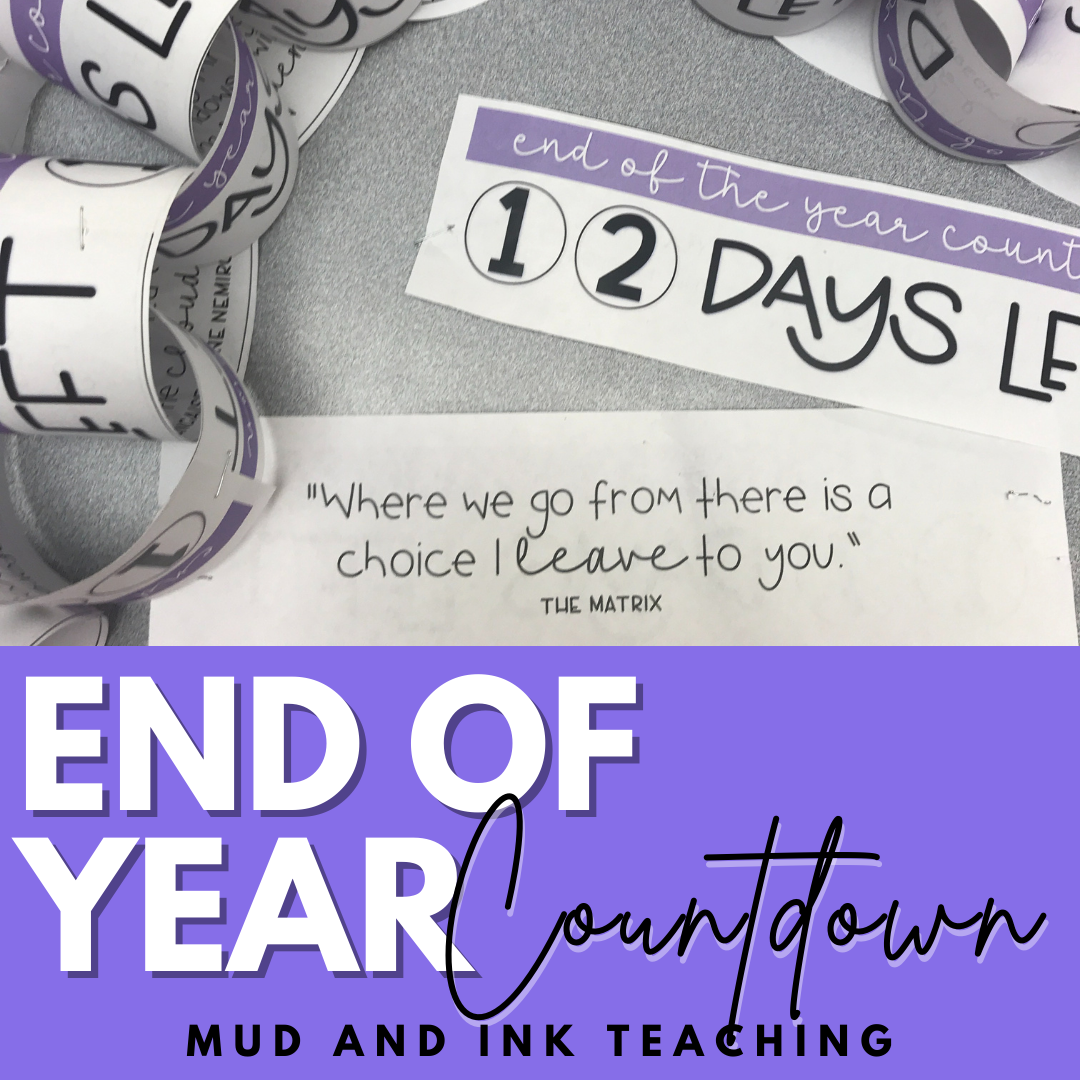

End of Semester Ideas for ELA

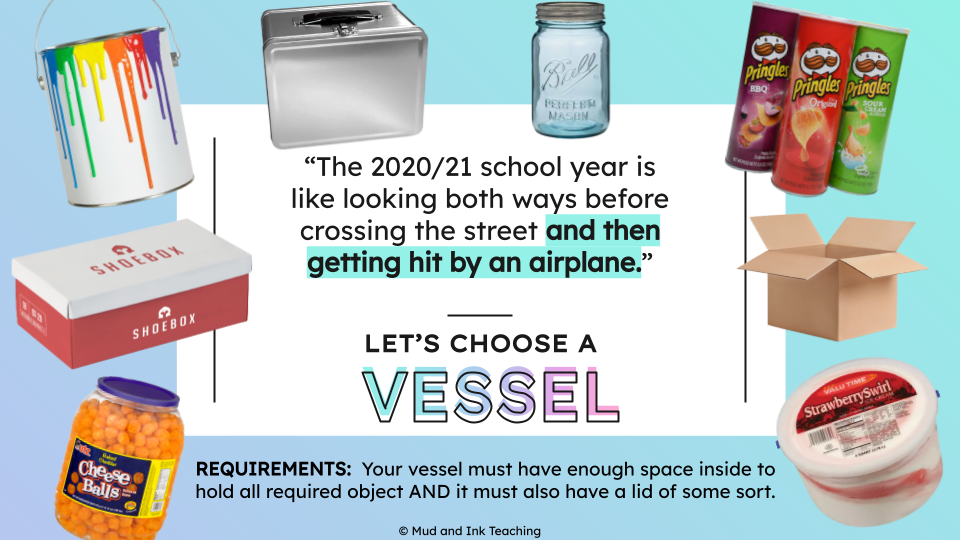

Things get hectic at the end of any semester, but not if you have the right game plan! For teachers in the ELA classroom, we have five sure-fire ideas to keep you focused and doing the most authentic work that you believe in.

YOUR END OF YEAR PLAN: DELIVERED.

There are so many considerations at play when wrapping up the end of a semester in your English Langauge Arts class. Whether you’re ending the semester before a break, ending the semester with awkward time after a break, or ending the course altogether, we have to balance the extra tasks on our shoulders at this time of year (contacting parents, finalizing the gradebook, dealing with students who are DONE, etc.) as well as the academic side of things. Oh, and if you’re trying to enjoy some holiday festivities and/or pack for your first vacation in a long time, you’ve also got to figure out how to be a PERSON right now, too.

So, I reached out to some teacher friends of mine to bring you our BEST tips for the end of the semester in ELA. Here are the suggestions that will help you keep everything straight, organized, and most importantly, meaningful for both you and your students.

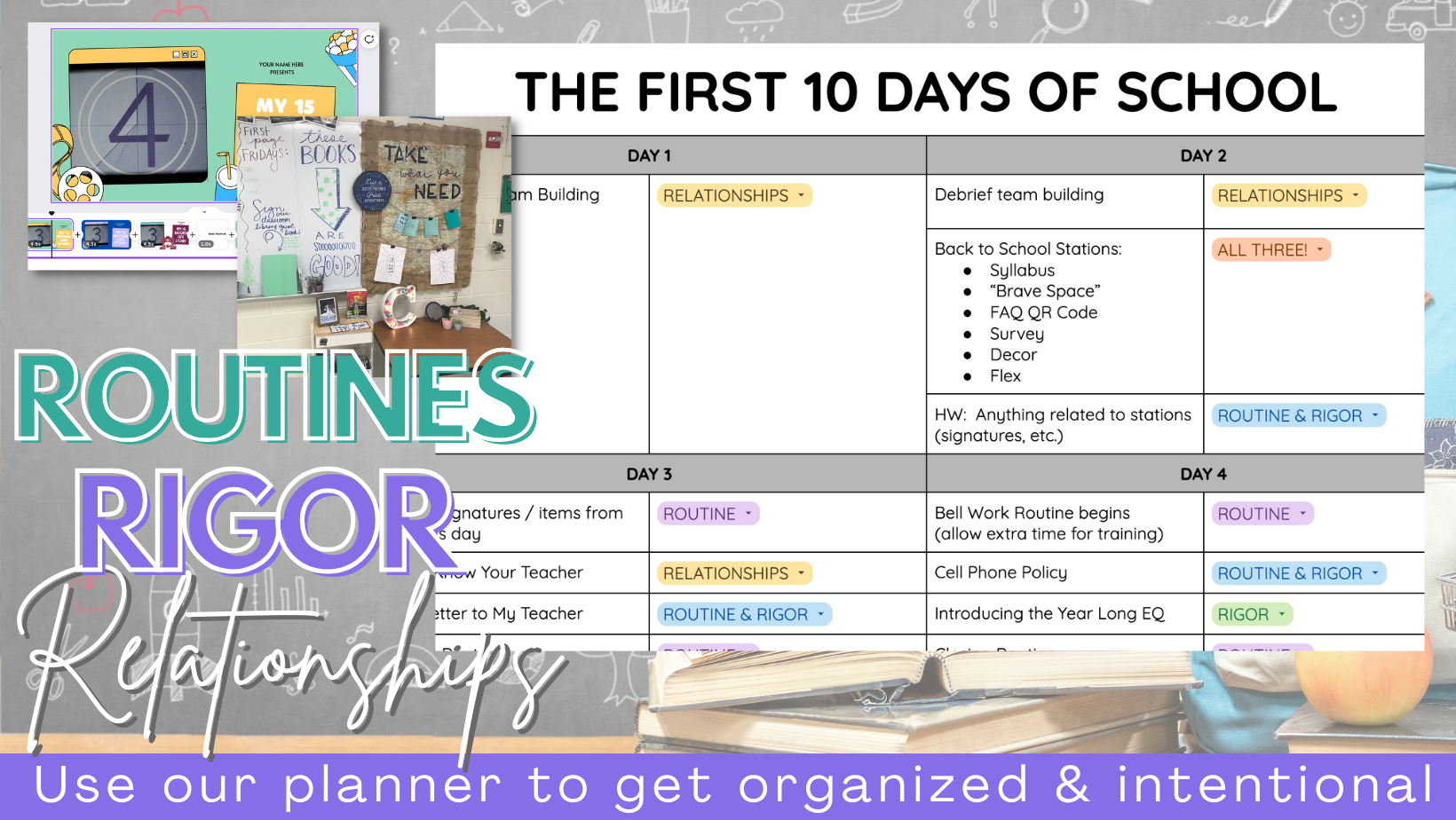

1. END THE SEMESTER WITH A PLAN FOR NEXT SEMESTER

Need help? I’ve got you covered! CLICK HERE

You heard me. And I know this sounds like WAY too much to do, but please believe me when I say that your restfulness over the break will exponentially increase when your first 1-5 days for your return are handled. So, as you plan your end of the year to-do list, carve out a few hours to plan, decide, print, and schedule everything you need for AT LEAST the first two days when you return. Here are a few things to get you started:

Reestablish (if mid-year) or establish (if start of year) classroom culture and energy with a fun get to know you activity

Use poetry as a vehicle for students to reflect on their past and set goals for the future

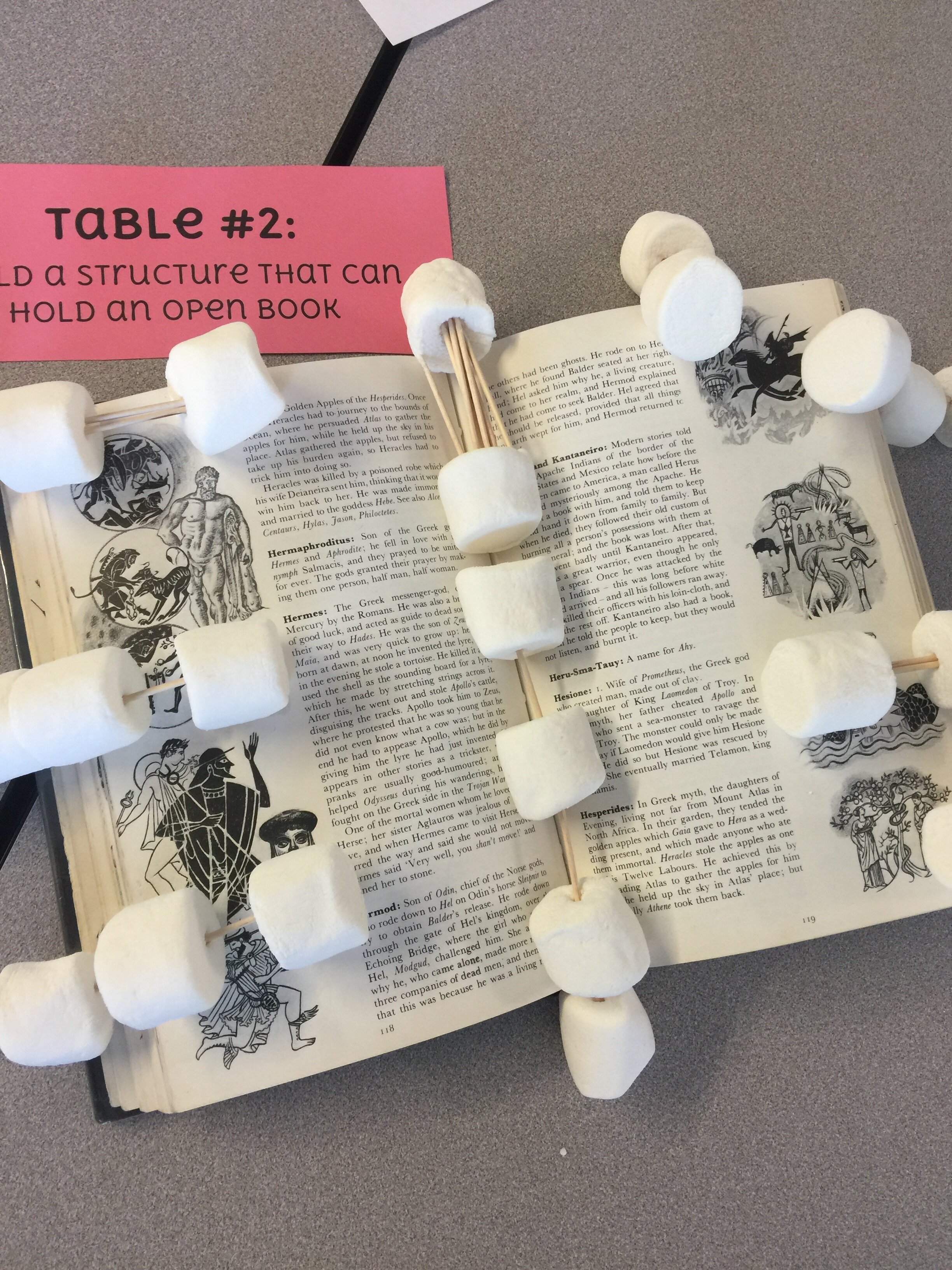

Establish or revisit expectations for group work using marshmallows and toothpicks

Introduce a bell work routine that will help create a calm, organized start of class for the rest of the semester to come

Once your planning is done and you’ve committed to the plan, finish up the semester, close your laptop and TAKE YOUR BREAK knowing that you’re already good to go upon your return. Go ahead…take that sigh of relief!

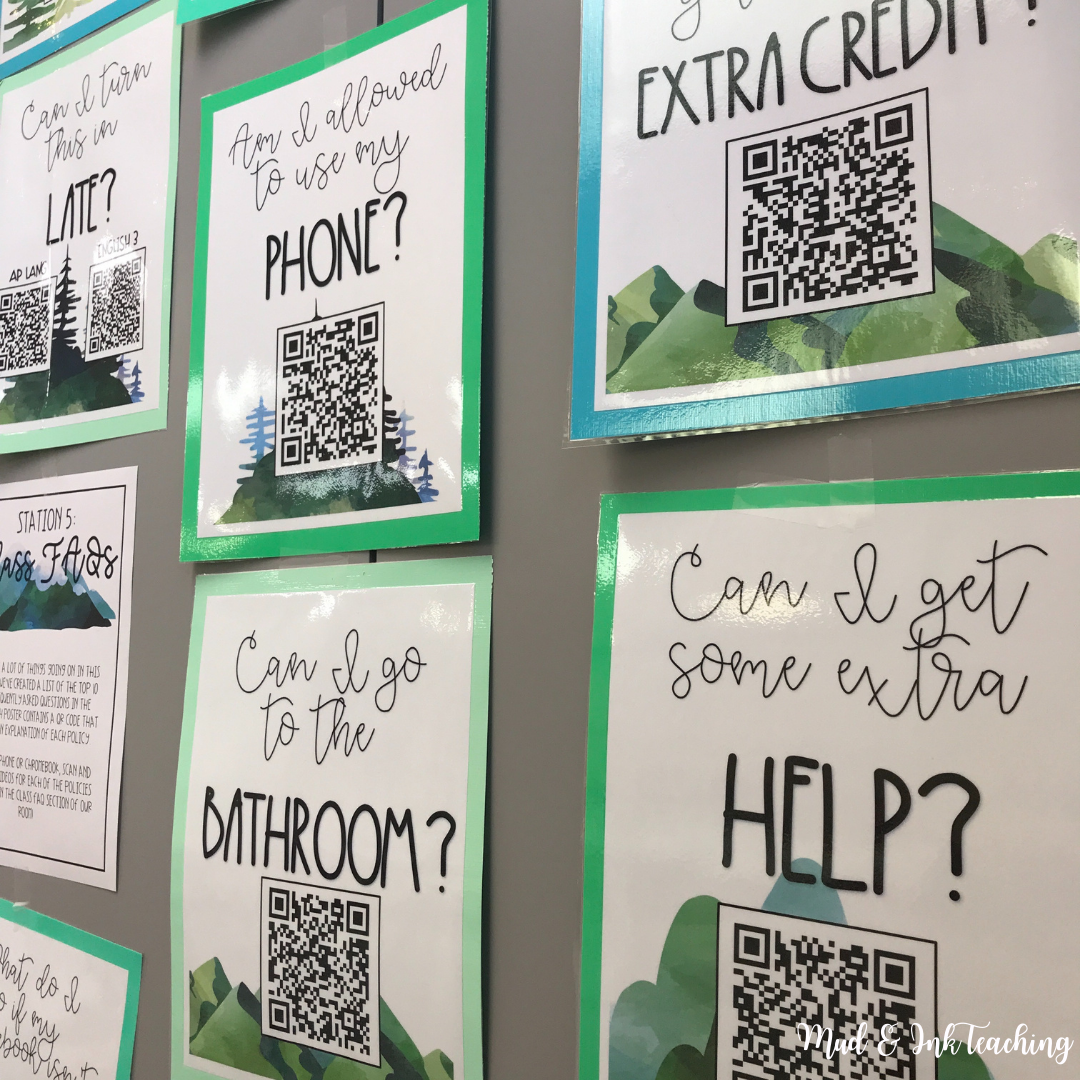

2. MAINTAIN STRUCTURE, BUT STILL HAVE FUN

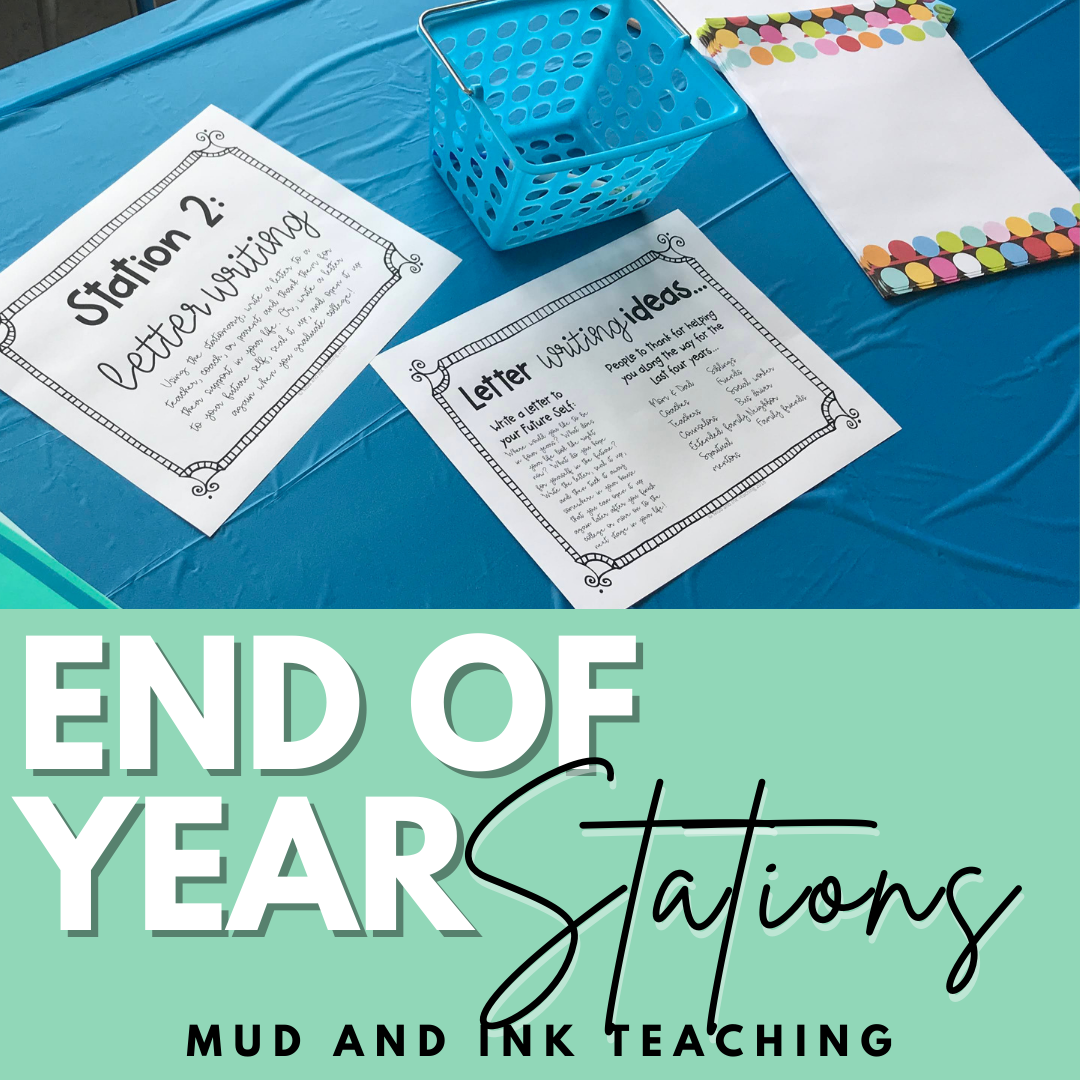

Stations: they’re our educational equivalent of fashion’s “little black dress”. They do, in fact, go with everything. If we love using stations at the beginning of the year so much, we use them to introduce new concepts, to revise writing, and even to do close reading, then we should definitely be using them at the end of the year!

Stations offer us a tight structure (super important when summer is getting close and closer every day), while also allowing us plenty of room for fun. I’ve done stations for as little as one class period and for as long as four days! I’ve compiled my fourteen favorite stations activities here for you to check out.

3. AUTHENTIC WRITING ASSESSMENTS

“Ms. Barbour, thank you so much for not giving us a boring final exam before Winter Break!”

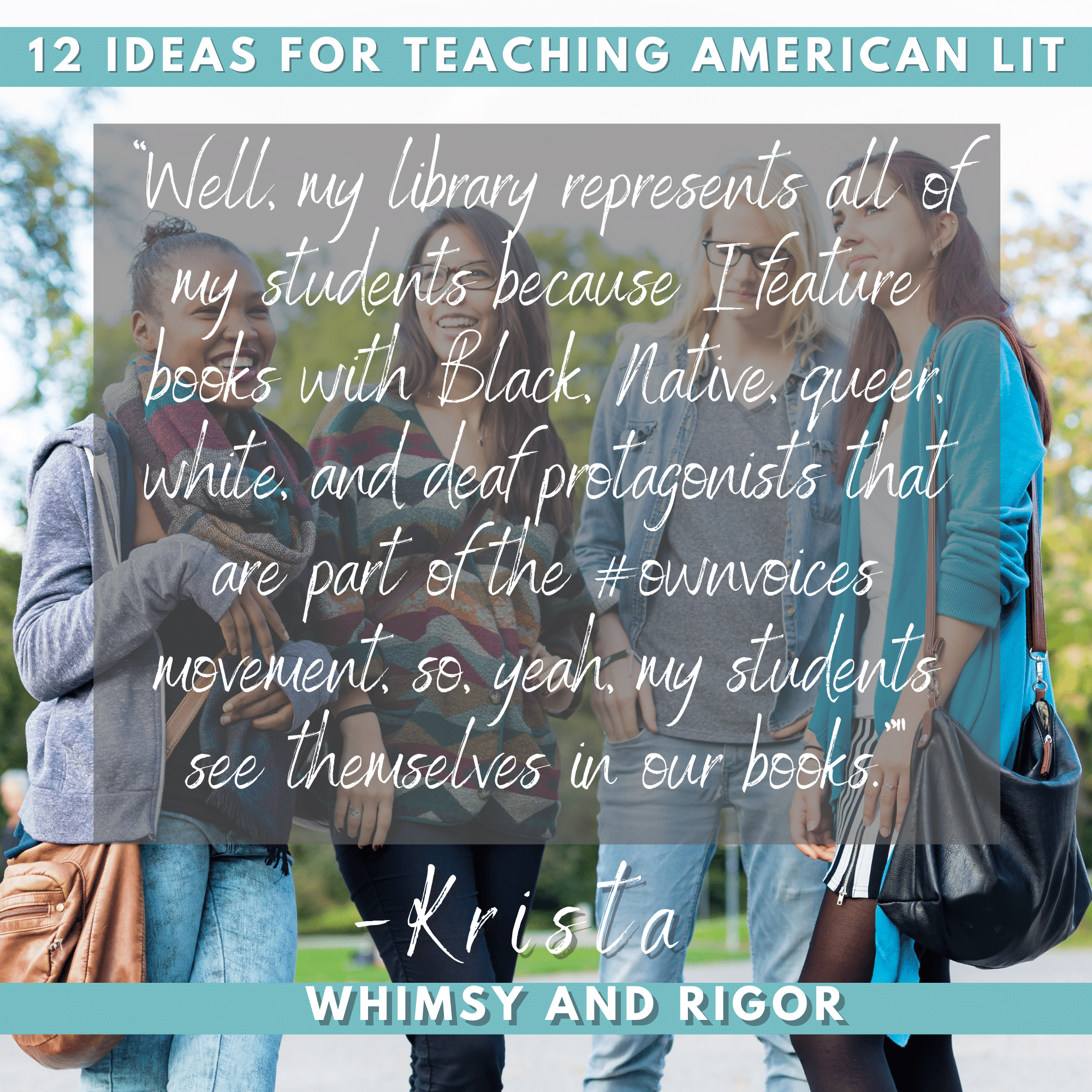

Krista Barbour from @whimsyandrigor hears this every year from her middle school students and that’s why she knows her decision to ditch the final exam was the right one for everyone.

So, what does she do instead? An authentic assessment embedded in a piece of writing students are already engaged with! In this YouTube video, Krista goes over what kinds of topics can be assessed (apostrophes, commas in a list, paragraph breaks, etc), how to first incorporate formative assessments for feedback, and then how to seamlessly assess their application of the skill in their creative or analytical writing. Krista (and her students!) love this strategy because it is 100% authentic. NO in-a-vacuum quizzes. NO can-you-memorize-these-rules tests. The students learn a skill, practice with a teacher, apply it to a piece of writing they actually care about, and are assessed in their practical use of the skill. It’s seriously a winner and BONUS! there are no stacks of exams to take home and grade over our much-deserved Winter Break!

For Krista’s students, the semester always ends with the culmination of their novel-writing project. Like, legit 10,000+ word novels that students wrote in 30 days. Talk about authentic writing! If you are curious about how this project works, how Krista survives, and how the students thrive during these 30 days, check out this blog post or peruse all the resources right here!

OK-teachers YOU got this! And even if you barely make it across the finish line in December, you still did it! Now, grab a good book, some delicious treats, and relax. No one deserves it more than you. Plus, you cleverly ended the semester with nothing to grade! Go you!

4. A LITERARY QUOTE BOOK

The end of the semester can be a whirlwind because often students end in different places or are sometimes missing various assignments. Samantha from Samantha in Secondary combats this by assigning a high-interest, self-paced project so students can review concepts learned in class while still doing something creative and engaging.

A literary quote book is a great way to see what stuck with students in an authentic way. Students peruse all of the texts covered in the assigned time period (for instance, a semester alone or even the entire year) and find relevant quotes that stuck out to them. They illustrate the quote either digitally (using stock photos with text overlay) or on paper with their own imagined illustrations to compile a small book. Then, students connect each quote to a broader theme and explain the connection. This process easily combines creativity with an extra layer of rigor. Have students share their final creations to see how their chosen quotes compare to others. This creates an opportunity for rich discussion about the text without much effort on your part!

You can grab this no-prep project here (with rubric and examples created for you) or come up with your own vision for this project. You will love seeing what your students create!

Betsy, from Spark Creativity, will never forget the end of her first term in teaching. She assigned a differentiated project with six different options and six different rubrics. She had four classes of projects to grade, final percentage tallies to figure out, and individualized grade report comments to write for every student. Plus, she was the varsity head coach of a sport at the time, and seemed to spend every afternoon stuck in traffic on the California freeways with my team. Then her computer crashed.

5. DON’T COLLECT A PROJECT ON THE LAST DAY

Betsy, from Spark Creativity, will never forget the end of her first term in teaching. She assigned a differentiated project with six different options and six different rubrics. She had four classes of projects to grade, final percentage tallies to figure out, and individualized grade report comments to write for every student. Plus, she was the varsity head coach of a sport at the time, and seemed to spend every afternoon stuck in traffic on the California freeways with my team. Then her computer crashed.

Ahhhh…. The memories. So today she’s sharing a simple trick she learned the hard way. By all means, finish the term with an awesome creative project. A poetry slam, a class play, a literary food truck, an escape room project, a student podcast project. But make it due at least a week before the term actually ends!

During the last week, try to avoid collecting more major work to grade. Use that week for a short stand-alone unit you’ve been wanting to find time for. Perhaps choice reading, listening and responding to podcasts, viewing powerful Ted talks, diving into a life skills unit, or something else you’ve been dreaming about. Check in with kids about missing work, shore up your plans for the next term, and get your grading and averages done without adding more and more to your list.

6. REFLECT ON THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY

The end of the semester is always an exciting time but can also be pretty stress-inducing as well. When the dust has settled and she’s feeling somewhat calm, Molly from The Littlest Teacher likes to take some time out and reflect on what went well, what didn’t, and what she’d like to implement for next semester.

Sure, this reflection can be done during your prep when the new semester or year starts, but Molly has found that her reflection is more thorough and honest when everything is fresh on her mind.

You’ll want to prepare a list of probing questions to guide your reflection session. Ask yourself things such as, “What do I want to do more of next semester? Less of?” “What was the most successful lesson I taught this semester? What made it effective? How can I duplicate this lesson with next semester’s material?” “What was the hardest day this semester? What made it so hard?” “What areas do I want to simplify going forward?”

Find a quiet place and time where you feel focused and clear. Grab your list of questions, favorite pens, and favorite drink. Plan to actually write out your answers, not just think over them. As we English teachers know, there is value in journaling. Also have your master to-do list ready, so you can add to it all your exciting plans.

Molly created a free goal-setting workbook just for teachers that will guide your reflection and self-evaluation and help you set some clear goals for your best semester ever. Be sure to grab it to create a blueprint that’s unique to you and your ELA classroom.

NEED MORE IDEAS?

I’ve got you covered! Check here for more end of year teaching ideas and organizational tools.

KEEP READING…

4 AP Lang Skills ALL Students Should Learn

AP Language and Composition shouldn’t be the only place where students learn certain skills. In fact, these skills are so important, they should really be spiraled down into all of the grade levels leading up to Lang. Here are my top four recommendations to consider in your vertical articulation in your English Department.

I am a firm believer that any student who wants to take AP Lang and feels adequately prepared for the challenge should be allowed to take the class. That said, I spent the majority of my career in non-AP classrooms, and didn’t really know what was going on behind the AP curtain until I went to my first APSI (Advanced Placement Summer Institute). There are so many things that I’ve witnessed beginning Lang students struggle with that could easily be worked on and developed in the courses leading up to it. If you’re in a place in your career and curriculum writing journey where you’re looking to make some adjustments that help increase purposeful rigor, here are the skills to focus on.

This blog post is written in collaboration with Dr. Jenna Copper who has written her post on this same topic, but with a focus on preparing students for AP Literature. Between our two posts, you’ll have your students more than ready to embark on their AP journey in their English courses!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

Sometimes it can feel like there’s only time to practice analysis during summative writing assignments. If we truly want to see students grow in that area, however, we must create more opportunities within units to let students practice true analysis: discovering how the pieces of a text work together to create a whole. In AP Lang, this is done almost exclusively through nonfiction and other types of media that showcase an argument.

Rhetorical analysis is worth tackling at the younger grades, and I mean spiraling those skills beyond defining ethos, pathos, and logos. When we introduce rhetoric as a concept without the skill of analysis, there’s a lot of backtracking that needs to happen. Rhetorical analysis is not just identifying the parts (labeling ethos, pathos, logos, personification, etc.) but connecting those pieces together to figure out how they impact, shape, and build an argument.

My favorite way to introduce rhetorical analysis to students is not by showing commercials and defining the appeals. Instead, I introduce the rhetorical triangle, the argument as a whole, using a song. “Be Our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast is the perfect example of the rhetorical situation and the rhetorical triangle. Why would Lumiere use humor at this moment to convince Belle to stay? Why would he flatter her? Why would he establish his reputation as an excellent host? These “why” questions take students away from identification and toward analysis from the start. I wrote all about it and have a free sample lesson in this blog post!

I’ve even had fun (gasp!) with students practicing rhetorica in a low-stakes gameshow that I like to call: The Spare Change Gameshow. Students are faced with fun, friendly prompts and have to practice building their argument based on whichever rhetorical skill we are working on at the time. You kids will love this, and all you need is some spare change!

BUILDING / TRACKING A LINE OF REASONING

If you’re unfamiliar with the term “line of reasoning”, that’s okay. It’s a relatively new term, but it's something we’ve been teaching in writing for a long time. A line of reasoning is the thread that connects the most important structural pieces of an argument together: the thesis, the subclaims, the transitions, and all of the commentary that explains the connections that you are assembling with these pieces.

When introducing this as a concept (this is assuming students already know that there is a connection between their claims and subclaims), is through socratic seminar and fishbowl discussions. I present students with a big question and let them start tackling it. I map their conversation as they speak, tracking the beginning idea, the supporting comments, the changes in direction, the jumping off in a new direction moments, and then, I show it to them. I show them a sketch-noted, mapped conversation and discuss the line of reasoning from an initial claim to where we ended up. Discussions are messy and reading this map is often a bit confusing, but that leads us directly into a conversation about successful writing. Effective, written arguments are not the same as casual, organic conversation. Both have a line of reasoning, but the written one, the one that they are charged with completing, must have a carefully organized plan so that line of reasoning is clear, coherent, and persuasive. Our discussions eventually get somewhere deep and meaningful, but there are a lot of distractors along the way. By making this concept both an experience and something tangible they can see and hold, it helps students start to wrap their heads around this concept.

USING EVIDENCE

Teaching students to use evidence is just as important as teaching them to find evidence. Using evidence is where we find students struggling, and this directly links back to my previous two points: practice with analysis and the line of reasoning.

Accumulating some effective sentence frames is a great way to help beginning writers do this. Also, I’m here to let you know that it’s okay if the phrases used to present their arguments are less than desirable. I know that “this quote shows” is pretty annoying, but if that annoying phrase helps students get to the analysis part of that sentence, LET IT GO. Sometimes, phrases like this are just little bridges that help students get from the evidence to the commentary and analysis, and the more we harp on what phrases NOT to use, the more time and energy students spend on phrasing rather than attacking their arguments.

Coaching them with alternative options helps them get better. Instead of getting riled up, offer them frames like this:

The repetition of the word “_____” in this sentence is an indicator of the tone shifting from __________ to _________. At first the language was ________, but then the speaker starts repeating “_______” changing the energy of the conversation to ________________.

By using a (adjective) type of imagery here, the speaker reveals ___________.

Despite ______________, the speaker still argues _______________ in this line. This is important to note because _______________.

We even do this kind of practice in something I call a “paragraph chunk quiz”. On my podcast, Marie and I talk extensively about using sentence frames for formative assessment in our Masterclass: Down with the Reading Quiz.

CLOSE READING (FOR A PURPOSE)

Oftentimes, our English classes at the younger levels get bogged down with time spent clarifying plot points of the novel we’re reading in class. Monitoring students as they follow reading calendars and making sure they’re on pace is a trying task. But here’s where everything changed for me: shifting my priority to close reading.

The key to effective close reading lessons? A focused, limited purpose. When we read A Raisin in the Sun Act 1 Scene 1, we spend an entire class period close reading the Ruth and Walter scene where they fight about eggs. We watch the evolution of the eggs, the mentions of them and how they shape the tone and energy of the conversation. We walk away from that one day, that one, tiny moment of text, with a deep, layered understanding of the relationship between these two characters. Students are able to write about what the eggs symbolize and practice the skills we’ve been talking about here (analysis, using evidence) because we’ve been nose deep in the moment. You can take a look at all of my Raisin resources right over here!

By having close reading templates on hand, I can create these lessons quickly and effectively. Whether you can practice close reading with nonfiction, within novel units, with poetry, or other pieces, this is a powerful strategy to regularly use in preparing students to be stronger readers and writers as they move up in their English Language Arts journeys.

For more tips and ideas, be sure to check out Jenna Copper’s post in our collaboration between AP Language and AP Literature.

5 Common Mistakes Teachers Make When Teaching Figurative Language

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

I want to be very honest about this: I struggled writing the title of this article using the word “mistakes” because I don’t want teachers to feel like there’s one more thing I’m doing wrong. That’s not the heart of this at all. And let’s be perfectly clear: I’ve made ALL of these mistakes MULTIPLE times, and the reason I’m writing this now is that time, experience, training, and more experience have taught me more effective ways to do a part of our job. I wish I would have recognized these things about my attempts to teach figurative language earlier in my career. It would have prevented me from a lot of self-doubt and helped me grow my students into much more critical thinkers.

None of these “mistakes” are harmful to students. And if you’re finding these methods to be highly effective for your population, by all means, keep it up! But if you’re feeling like this is the 1,000,000,000th time you’ve tried to get kids to define “metaphor” and it’s still not sticking, stay with me.

Let’s start with our WHY

Always start here. Why do we teach the terminology, examples, functions, and use of figurative language in literature and poetry? For me, it boils down to a few important things:

These devices create an intentional effect. Analysis of the effect is important in understanding the message, the purpose, and the experience the audience is supposed to have.

These devices contribute to character development. If we value character complexity and development, being sensitive to the nuances in the details authors use to describe them requires an understanding of figurative language.

Many of these literary devices overlap with our study of rhetoric. Recognizing the tone of a particular metaphor or simile used in a speech, commercial, or other argument is important, so it’s highly valuable that this practice overlaps into two skill areas.

ONE: Rote Teaching Terminology (in isolation and otherwise)

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

Well, the first issue here is that language isn’t logical. And what we actually end up seeing is that the amount of time and energy we place on learning terms tells students that this is the most important part of the process. We know this is not the case (go back and look at our WHY), but in our teacher minds, we think: if they can’t identify a metaphor, how can they ANALYZE a metaphor?

I use to think this too. But then, after an Advance Placement Summer Institue, I was convinced to let go of terminology and see what happened. While close reading chapter 1 of The Great Gatsby students pointed out this line: “Two shining, arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face and

gave him the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward.” The students noted the use of the phrase “arrogant eyes” and debated how it should be identified. Was it personification? Eyes are a non-human object and certainly can’t possess the human trait of arrogance. Was it diction? Specific word choice Fitzgerald was using to create an effect?

I interjected and asked, “Tell me this: if you didn’t have to label the device Fitzgerald is using here, what would you say about this phrase anyway? Or if I told you that both labels work equally well, what do you have to say about the effect they have on characterizing Tom?”

I realized in this moment how little the term actually mattered. What mattered was that they did identify a critical description of a character. Call it diction, personification, description, connotation — that didn’t really matter in the end. But what I also realized is that students who get stuck here at this step, choosing the right term, would rarely make it to the next (and much more important) step of analyzing how this orients the reader to Tom’s character.

Releasing the pressure off of students to "correctly” identify figurative language terms might just help us move the conversation into the harder task. I give you permission to take your hands off the wheel a bit and instead of drilling them with terms, give them a word bank. Build a class website full of rich beautiful examples that you see all throughout the year. Correct students when an interpretation is completely off, but only when it has prevented them from accurate and thoughtful analysis.

NEED HELP KEEPING THE BIG PICTURE IN MIND? YOU NEED AN ESSENTIAL QUESTION AT THE HEART OF YOUR UNIT.

THE ESSENTIAL QUESTION ADVENTURE PACKS ARE HERE TO HELP.

TWO: Assessing Definitions

Let’s go back to our WHY again: if the goal of teaching figurative language is to move students toward rich analysis, then what does assessing definitions do to help us reach that goal? Let’s look at these two definitions as an example:

EXTENDED METAPHOR: a metaphor introduced and then further developed throughout all or part of a literary work, especially a poem

SYMBOLISM: the practice of representing things by symbols, or of investing things with a symbolic meaning or character.

By definition, these two devices seem to have clear differences but put into practice, students have some good questions about the blurry line between the two. In Julia Alvarez’s novel In the Time of the Butterflies, the butterfly serves as an extended metaphor (or is it a motif?) throughout the novel. Students asked me every year, “But isn’t the butterfly a symbol for the girls and the rebellion?” And year after year I carefully explained that metaphor was a better term to use because metaphor requires comparison whereas a symbol is more of a stand-in. The layers of meaning are comparative to the sisters and their experiences and metamorphosis as they grow into rebels.

The famous “Green Light” of Gatsby’s world is a symbol, though. It’s an object that pretty much means the same thing throughout the text and represents a wide variety of interpretations of ideas and emotions for Gatsby.

So here’s the mistake I realized I was making: this level of understanding how language devices function, especially in long works (as opposed to poetry), cannot be assessed by asking kids to define terms. Also, as outlined above in Mistake One, does it really matter? Does it really matter if a student discusses the butterfly as a symbol instead of a metaphor? Or the Green Light as an extended metaphor instead of a symbol? If the analysis in the sentences that come after are spot-on, insightful, accurate, and lined up with the rest of the work, I think we should let it go. I’d rather spend time here, in the text, having hard conversations, than reviewing terms or assessing students on the definitions of terms.

THREE: Teaching Too Many Terms

If you’ve ever bitten off more than you can chew, you’re in good company here. I am notorious for getting super excited about a poem or a book and trying to teach ALL THE THINGS. My excitement and enthusiasm will make the kids engaged, write?

Oof. I couldn’t be more wrong. Too many terms in the lesson or even in the unit is a recipe for disengagement and burnout. This happened to me often with close reading things like Shakespeare or even other types of poetry. Repetitiotition here! Metaphor there! Synecdoche here! Allegory everywhere! Crash and BURN.

FOUR: FORGETTABLE EXAMPLES & Lack of “Flashbulb” Moments

If you haven’t yet read Keeping the Wonder, then maybe you haven’t stumbled across the concept of a “flashbulb” moment or memory. The authors write, “When we think about the moments that stand out in our memory, it’s clear that our minds hold onto the unusual or unexpected. By tapping into students’ innate curiosity, you can design memorable, meaningful learning experiences that captivate their interest and ignite their imaginations.” (Keeping the Wonder, 2021)

This concept is vital in our instruction of particularly important literary devices. I found that when I was scraping for examples to teach definitions or make flashcards on Quizlet, the examples were often unoriginal and oversimplified. Slowly but surely, I started building up a bank of device examples that were so powerful that they were unforgettable. My favorite flashbulb literary device lesson was in teaching juxtaposition, of all things.

This was our juxtaposition flashbulb moment: the ballet scene from The Phantom of the Opera. I haven’t taught the film in a long time, but the memory of this juxtaposition lesson is still crystal clear all these years later. I even get Facebook messages from former students every now and again about this, and it cracks me up! In the scene, the Phantom is chasing the stagehand (who knows too much) back and forth across the rafters of the stage. Below them, a spring ballet, complete with sheep, goats, and baby’s breath, is underway. As the Phantom closes in on his victim (darkness, impending death), the ballet swiftly picks up pace (spring, light, and full of life). The scene ends with a shocking murder of the stagehand, giving students the perfect moment to examine WHY the juxtaposition as an artistic decision works in the scene.

Trigger warning: This scene ends with a hanging

The success of this moment, of slowing down and spending almost two class periods on one literary device (which was not the original plan, by the way!) taught me, once again, that less is more. Did I cram through a huge list of lit terms that year? No. But did my student have a life long impression, memory, and deep analysis practice with one challenging device? Yep. And we still remember it.

FIVE: Missing the Structure of Spiraling

Vertical alignment might be one of the biggest struggles for English departments across the globe. In the coaching work I’ve done with schools, I’ve found that the single-most source of frustration for teachers is that they don’t actually have a hold on what students learned before they got to them or where exactly they’re headed after their class. Teachers crave autonomy, and rightfully so, but autonomy can quickly lead to isolation and problems with skill-building.

The instruction of literary devices and figurative language analysis should ideally be spiraled across grade levels with intentionality. When grade levels select texts, standards, and essential questions are built in curriculum design, this is a layer to consider adding. Here’s an example of what that could look like and figurative language focal points that would work nicely:

FRESHMEN:

Metaphor: Long Way Down

Imagery: Children of Blood and Bone

Point of View: Frankenstein

SOPHOMORES:

Juxtaposition: The Phantom of the Opera

Extended Metaphor: In the Time of the Butterflies

Personification: Fahrenheit 451

JUNIORS:

Symbolism: The Great Gatsby

Paradox: Macbeth

Parallel Plot Structure: A Thousand Splendid Suns

SENIORS:

Allegory: The Life of Pi

Point of View: Homegoing

Flashback: The Handmaid’s Tale

Clearly, these aren’t the only things that each particular unit would cover, but having in mind the flashbulb memory opportunities that naturally exist in each text helps spiral the skills. Now, each teacher knows where each of these devices is highlighted (we’re not skipping everything else, just giving extra attention to these each year), and can align their expectations of students accordingly.

LET’S GO SHOPPING

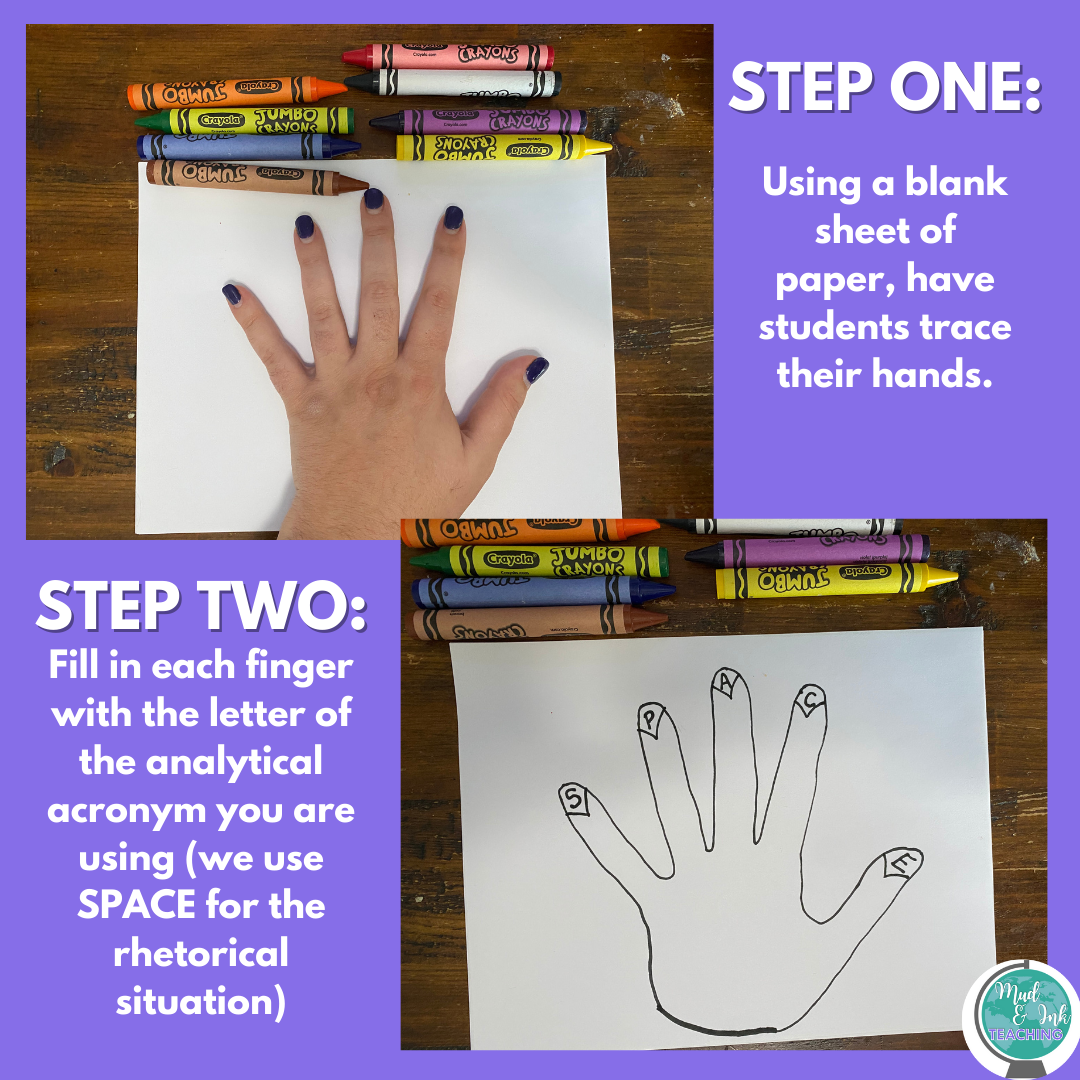

Rhetorical Analysis: A "Hands-On" Approach

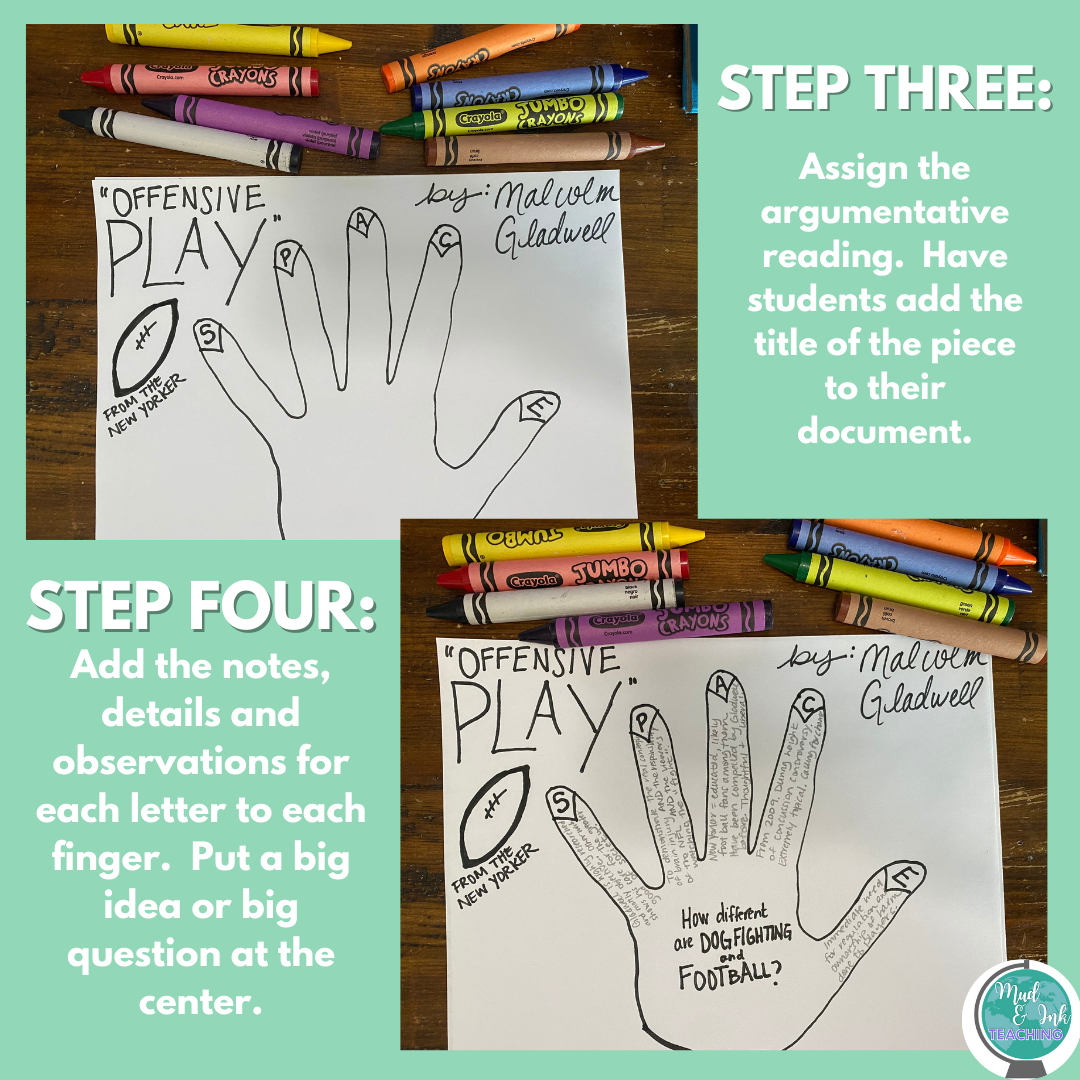

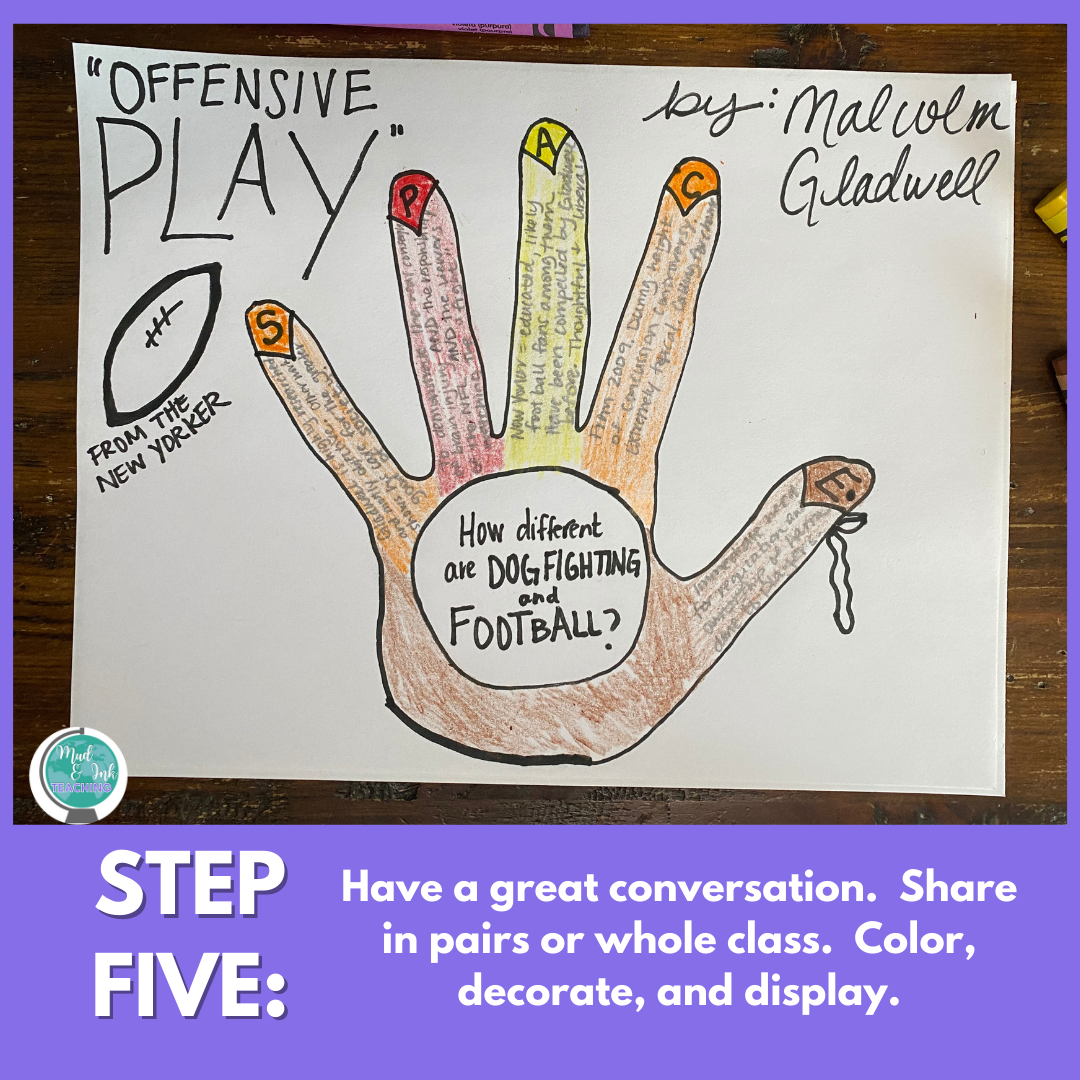

Keeping rhetorical analysis fun isn’t easy, but here’s a simple idea that requires no extra work on your end. Handprint or five-finger analysis is a memorable and creative way to analyze an argument and you can easily customize this organizer to fit any season or text you are studying.

Is it a pre-requisite that all English teachers tell bad pun jokes? I mean, I just couldn’t help myself when I was giving this article a title. Let’s get right to it.

Rhetorical analysis. Whether you’re introducing at the younger grades or a seasoned pro at AP Language and Composition, we all get to a point in the year when RA feels like a bit of a chore. There are only so many Disney lessons we can do before we need to really get down to the hard stuff, so what's a great way to shake things up without sacrificing rigor? Bust out the art supplies.

This is not the first time I’ve taken an analytical practice and attempted to make it more tactile (here’s where we made sensory bottles to imitate tone in poetry and Gatsby), and that’s because I’ve learned my lesson: IT WORKS. Moving an analytical, thinking task to a tactile experience is exactly what helps kids continue to push their skills and avoid burnout and boredom.

THE HANDPRINT ANALYSIS / FIVE FINGER ANALYSIS

Here’s what you’re going to need:

An argument to analyze

A previously taught & practiced acronym used for analysis (I like SPACE CAT)

A hand

A blank 8 1/2 X 11 sheet of paper

Coloring supplies (optional)

That’s it! I promised this would be low-maintenance.

And it works pretty much how it looks:

Assign an article, speech, commercial, or other arguments

Have students trace their hand on the blank page

Assign a letter of your acronym to each finger. If you’re using SOAPSTONE, you might need to use two hands or put some of the letters on the outside of the hand. I like to use the SPACE portion of SPACE CAT to practice the rhetorical situation. If you wanted to have students continue the analysis, they could add the “CAT” portion to the inside of the hand or the margins around the hand if you’d like.

Ask students to take appropriate notes in each of the fingers.

Teach your lesson as usual with sharing, discussing, etc.

Finish off the hand-outline with a seasonal turkey (if it’s that time of year) or simply have students color the hand into some other kind of animal or object that they desire.

Display proudly.

These kinds of activities are gold for you as the teacher. You are doing and practicing NOTHING NEW, but by changing the organization and appearance of the lesson, you will breathe new energy into your week and your students will keep giving you great work.

THANKSGIVING / FALL ARTICLES & READINGS

As I’m sharing this in mid-November, I’ll share some articles and pieces that work really well at this time of year. This activity is a wonderful pre-Thanksgiving break assignment and I’ve had a lot of success with the following readings:

“Offensive Play” by Malcolm Gladwell (Thanksgiving and football are a classic combination, but after reading this article, your students will have a whole lot more to say at the dinner table about dog fighting)

The President's Thanksgiving Day Address to the Nation from Lyndon B. Johnson (1963) A Thanksgiving message delivered only days after President John F. Kennedy was killed.

Why I’m Not Celebrating Thanksgiving This Year (VOGUE) A thoughtful piece from an indigenous woman’s perspective: what are we actually thankful for?

The Dark Side of Black Friday Stuff your belly and head to Best Buy to get in line…

However you use this activity and at any time of the year, I hope this brings a little life to your classroom without a lot of planning or prep on your end. If you try this activity, please tag me on Instagram @muandinkteaching to let me see how it went for you and your students!

And if you’re new here or new to teaching rhetoric and the rhetorical situation, I’ve got you covered. I’d love to send you a full lesson plan on how I introduce rhetoric using “Be our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast! This lesson has been downloaded by over 2,000 teachers! Good luck with your teaching rhetoric journey — its a worthy endeavor and I applaud you for your efforts!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

October Lesson Plans for the ELA Classroom

October is a rich month full of seasonal topics to layer into the ELA classroom. I’ll admit, though, I didn’t always think that seasonal activities were all that important in my classroom. Most activities felt cheesy or forced, but as I’ve grown as an educator, I’ve found that the right lessons at seasonally relevant times of year hold a special power and break from the typical everyday ELA lesson plan.

October is a rich month full of seasonal topics to layer into the ELA classroom. I’ll admit, though, I didn’t always think that seasonal activities were all that important in my classroom. Most activities felt cheesy or forced, but as I’ve grown as an educator, I’ve found that the right lessons at seasonally relevant times of year hold a special power and break from the typical everyday ELA lesson plan.

What’s going on in October that’s especially relevant for ELA? Two things are especially important for me: the study of gothic fiction and the celebration and recognition of Hispanic Heritage Month.

GOTHIC LITERATURE & HALLOWEEN

So much of the gothic literature novels that we have available to teach are really long and not always fitting at every grade level. Short fiction and mini units on the genre, however, are not to be missed.

A gothic MINI UNIT

If you have time to read Frankenstein or Jane Eyre, that’s wonderful. These stories are so profoundly unique in this genre and give students amazing opportunities to explore good and evil, nature vs nurture, and the complexities of the human condition. I’m guessing, though, that most of you don’t have the time for a full novel-length unit set aside for this genre, and that’s okay. A 3-5 day mini-unit can do the trick and still give students time to explore the genre through inquiry and come away with some new thoughts about their own lives and other genres that they will read in the future.

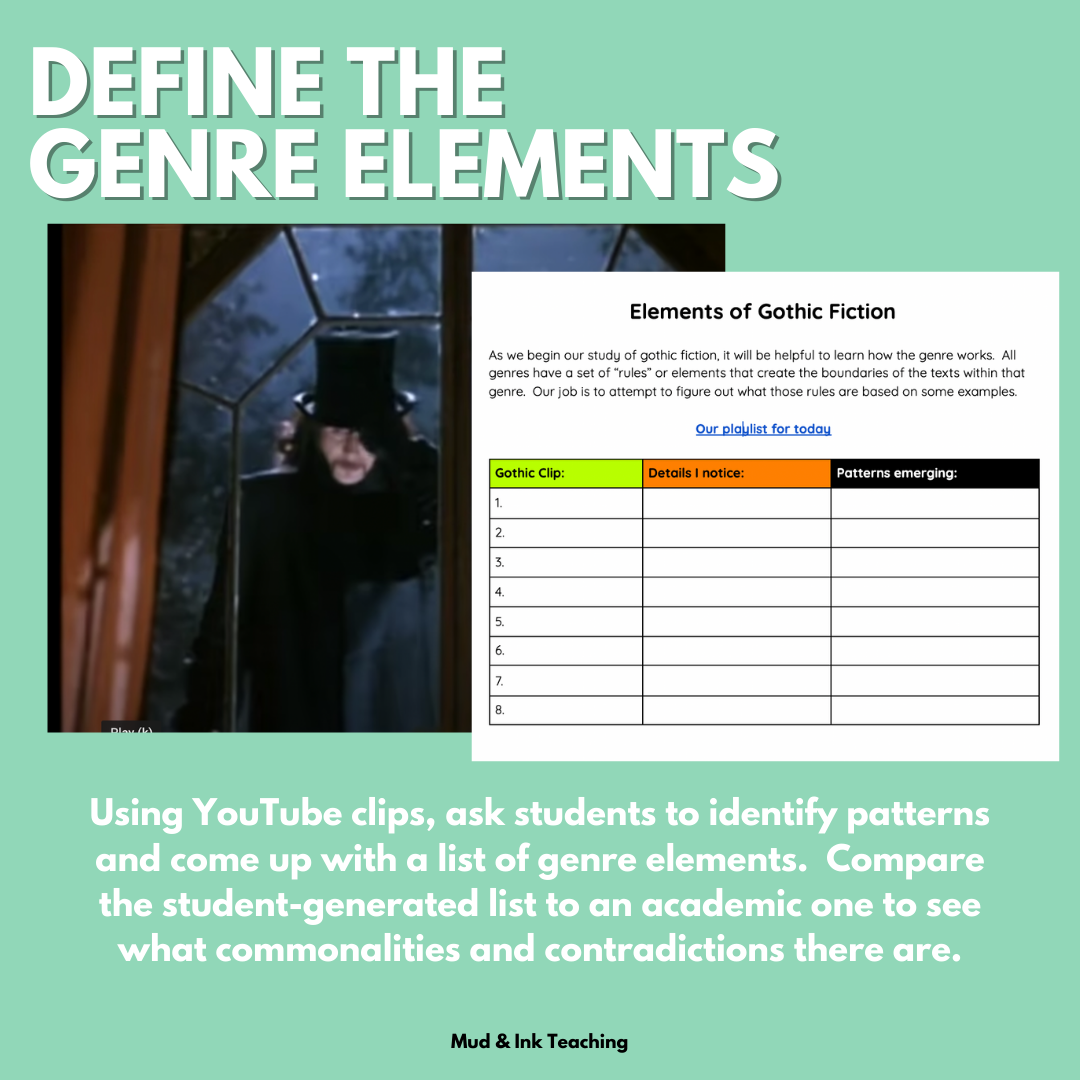

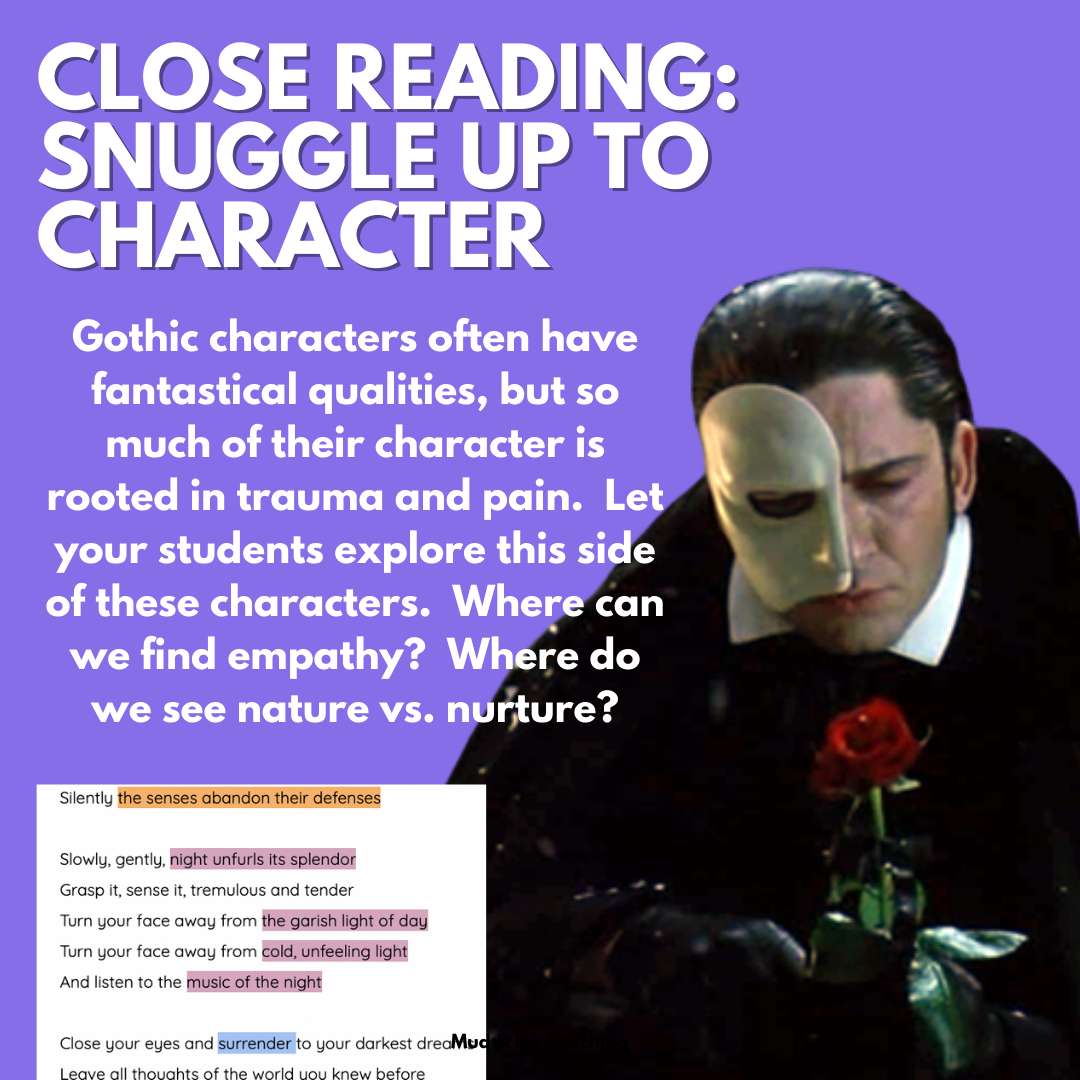

In all of my genre-based units, I tie them together with an Essential Question anchored in elements of that genre. I love the question, to what extent does gothic fiction reveal the human condition? Because we’re working within a genre, it’s powerful to have students investigate the elements or “rules” of the genre. I do this by sharing a playlist of YouTube videos and asking the students to record the patterns that each follows. What unites them? If these are all considered gothic, then what is gothic? We take a day to close read song lyrics from The Phantom of the Opera, and even do some writing of our own. By the end of the experience, we hold a class discussion (usually a fishbowl or Socratic Seminar) and discuss the question we started with: what have we learned about humanity by looking through this gothic lens?

A DIGITAL CHOICE BOARD

If you’re interested in exploring this Essential Question but need a more streamlined and less time-consuming way to explore it, I love the option of using a digital choice board for bell work or weekly assignments. A digital choice board is a slides-created document that has several categories and buttons for each category that takes students to a different article, poem, song, or other text to explore under the umbrella of an EQ or topic of your choosing. These take a while to make, but can be used year after year. If you don’t have time to make one, I’ve got you covered!

DISCUSSION OF COSTUMES & CULTURAL APPROPRIATION

Synthesis writing is a skill that we are always working on, and my favorite way to practice many of those skills is actually through the use of discussion. A timely and important topic for students to discuss is that of cultural appropriation and Halloween costumes. Back in the 90s (when I was a kid), we never talked about this, but as we grow more collectively aware social consciousness about correcting wrongs and “know better, do better”, this is a powerful topic to present to students. Using a fishbowl or Socratic seminar format, I present my students with 10-12 different articles all addressing the question: To what extent can cultural lines be crossed in costume? . After some time to read and prepare, we come together to discuss and figure out where the line is that shouldn’t be crossed.

MONSTERS & VILLAINS

Speaking of Essential Questions, the variety of options that tie in with this October season are plenty — especially those dealing with monsters and villains. I chatted with my friend Marie Morris of The Caffeinated Classroom about her 12th grade world lit course, and we brainstormed the coolest essential question for her to use for her course: Who will determine the fate of humanity: the heroes or the villains? In that episode, we talk at length about the many facets of what a question like this could look like in both a unit and a course — give it a listen!

A VARIETY OF MINI-LESSON IDEAS

If you still don’t know where to start, I have an amazing collaborative podcast episode to share with you that features six teachers across 6-12th grades and their unique and creative ideas for featuring gothic fiction and Halloween-related reading and writing lessons during the month. From 6th grade mood writing to a 12th grade villains course, these teachers have so many fascinating ideas to share. Cue this episode to listen to on your drive to work1

HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH

From September 15th to approximately October 15th, Hispanic Heritage Month is celebrated and recognized. Cultural heritage months are an amazing opportunity to highlight the voices and contributions of the community as long as we are working to also feature these voices all year round and not look to them as tokens for one month out of the year.

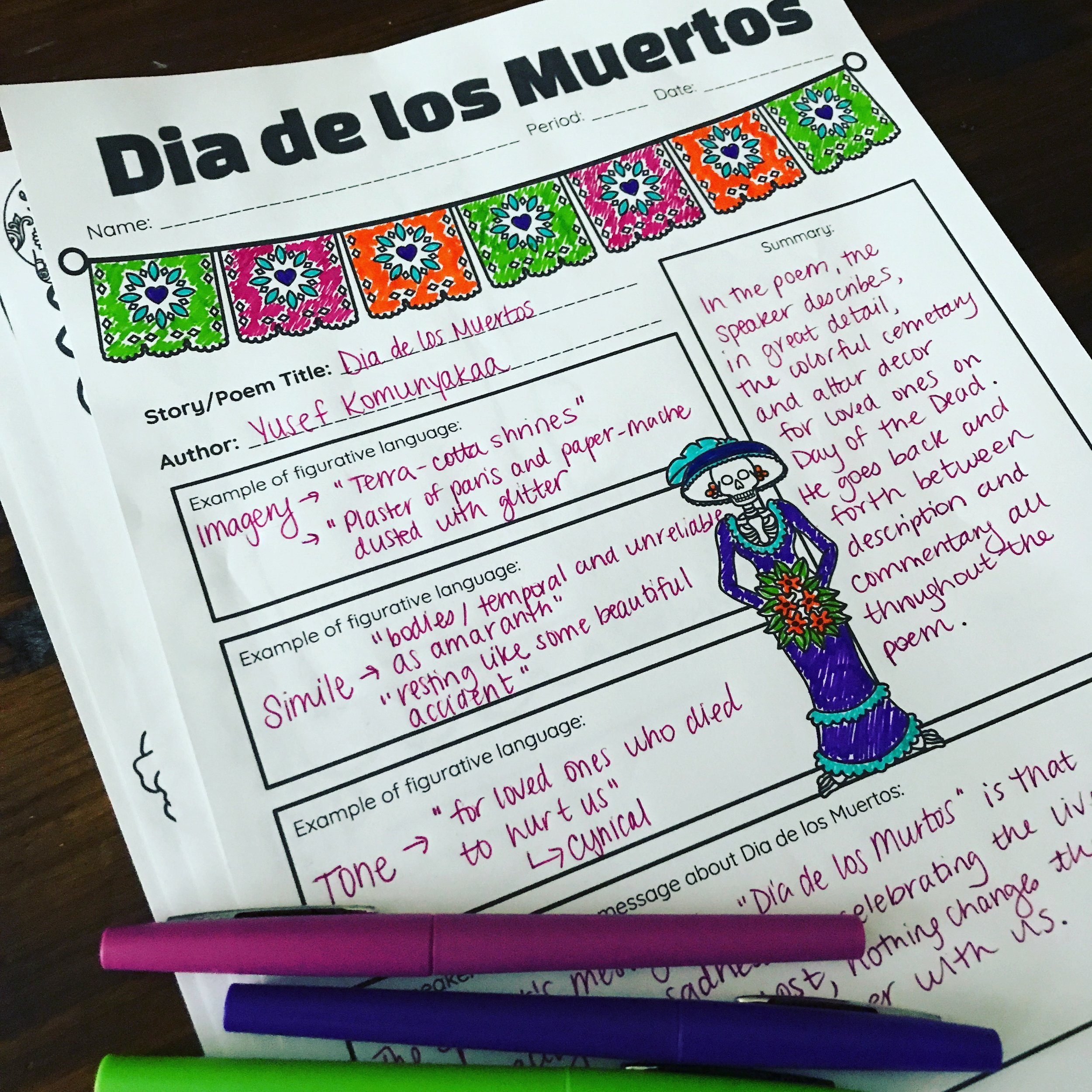

DAY OF THE DEAD

Dia de los Muertos is celebrated across Latin America at the very end of October and the beginning of November. One of the ways that I’ve tried to add more cultural literacy into my ELA classes is by blending learning about this holiday with a small poetry research project. After spending time learning about the traditions of the holiday, we read some poetry written for Dia de los Muertos. Next, each student selects a poet who has come before us to honor at our class ofrenda after conducting a small research project. On Day of the Dead, each student takes turns reading a signature (or even a lesser-known) poem from that poet and we remember the work of the great poets who have passed on.

LATINX VOICES

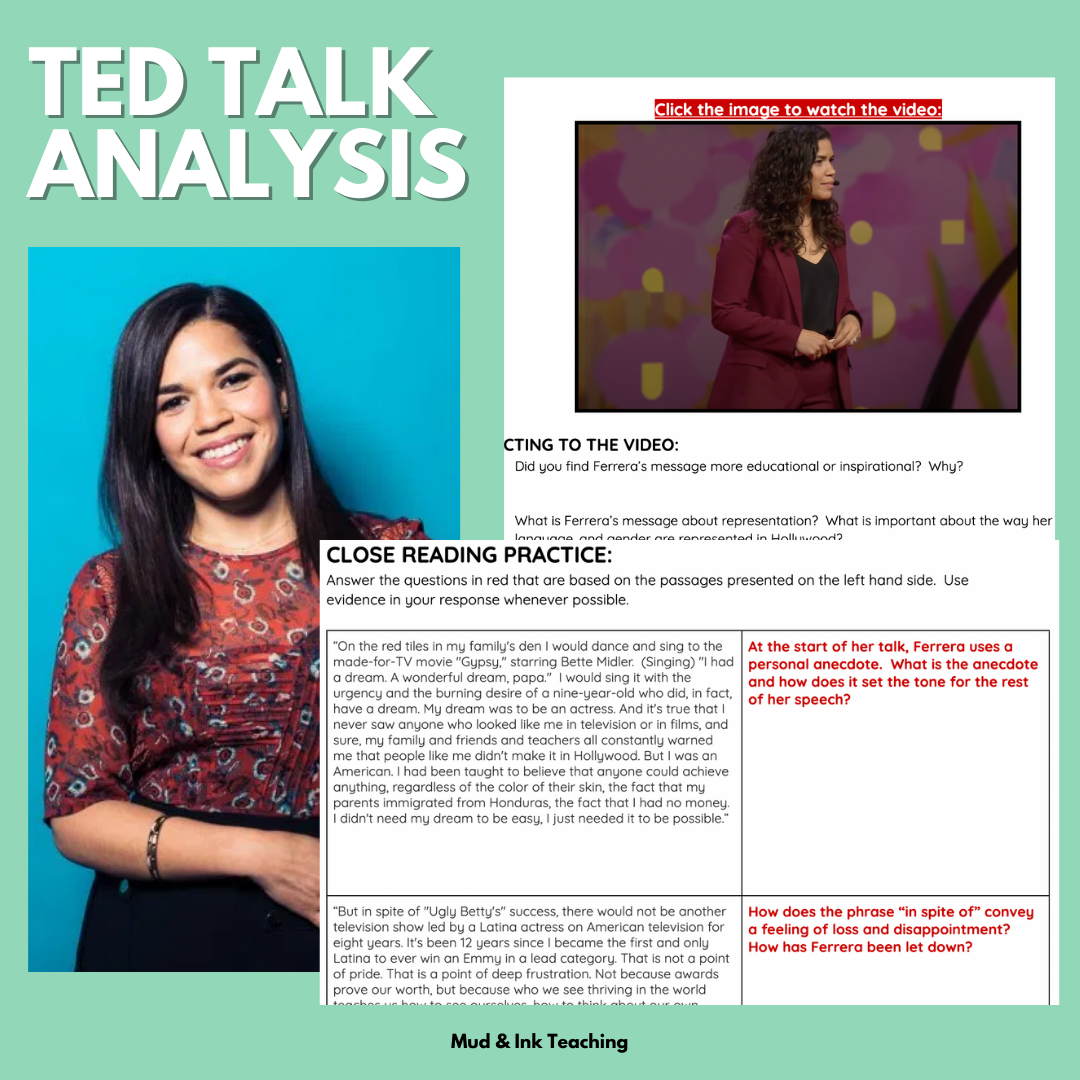

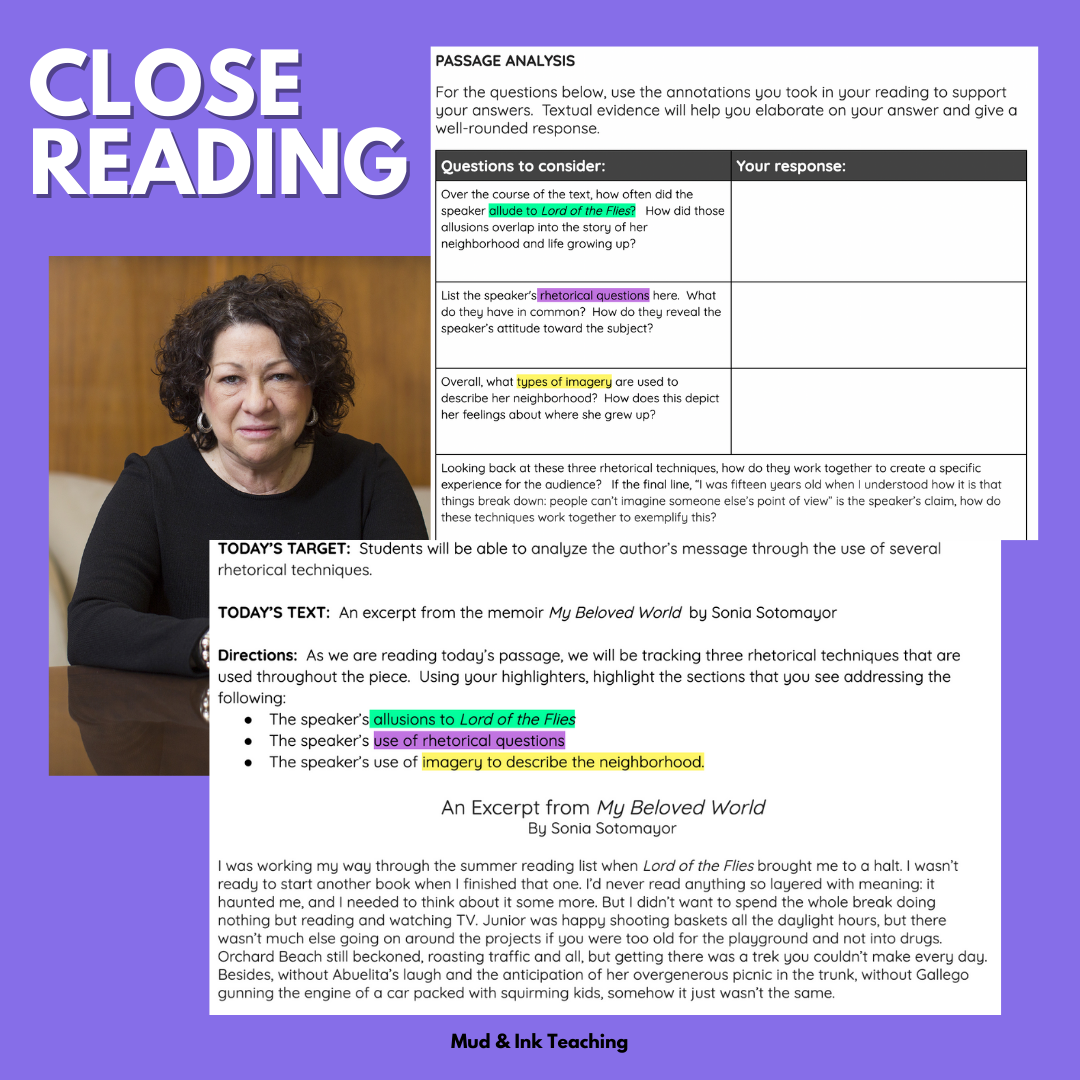

This is the perfect time of year to expose your students to some new LatinX authors through poetry, prose, nonfiction, and other forms of artistic media. If you’re currently working on practicing your close reading skills, you should check out this 5-week email series featuring Frida Kahlo, America Ferrera, Luis Alberto Urrea, Sonia Sotomayor and Richard Blanco. I’ve set up five free lessons for each writer that you can click and assign right away! If you like the idea of a choice board, I’ve got one of those, too. Students can explore shorter texts every day for 25 days completely independently using the choice board and the Google Form.

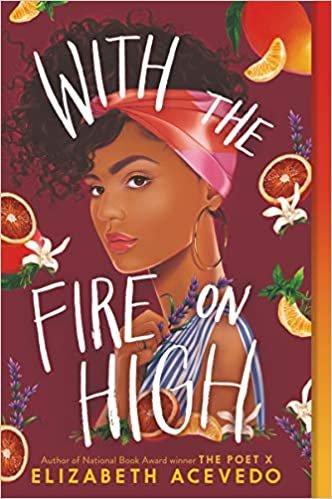

LATINX YA NOVELS

There are so many incredible up-and-coming writers for the young adult audience that are wonderful to highlight during this month during first chapter Friday events, book talks for independent reading, and more. Here are a few of my current favorites (each is connected to an affiliate link):

What are some of your go-to lessons for October? Which of these do you hope to try first? Let me know in the comments!

LET’ GO SHOPPING

Class Discussion: When to Stay Quiet, When to Speak Up

In order to facilitate high-quality classroom discussion, we must set up purposeful scaffolds on the front and back end of each discussion; however, in order for students to engage with the practice needed to meet these goals, we have to let the discussion happen organically and without our interference. These are the time that we stay in the background and when to speak up.

Let’s start by taking a quick poll:

Share your answer with us in the comments, and don’t forget to say WHY!

A: Fishbowl / B. Socratic Seminar / C. Philosophical Chairs / D. Online Discussion with Parlay

No matter which of the above is your jam, I think we can all agree that class discussion and the techniques we use to make them happen are all chasing after the goal of helping our students learn to have thoughtful discourse, how to talk about hard topics respectfully, and how to evolve their positions with both concession and deeper, more complex claims.

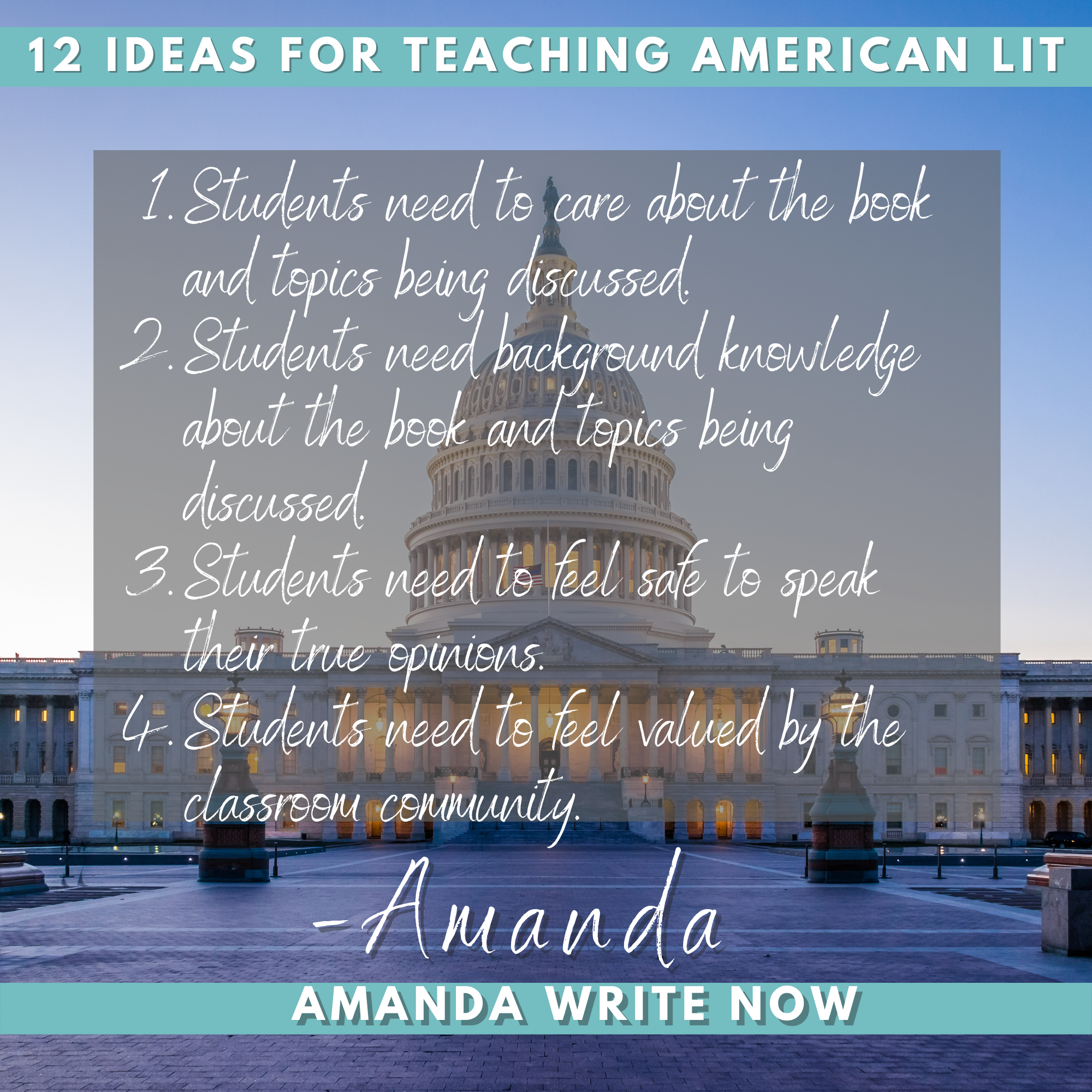

Discussion, whether it be at the beginning, middle, or after a unit of study, is a cornerstone in the pursuit of an inquiry-driven curriculum. Most often, discussions in my classroom are anchored to the unit essential question and present a series of sub-questions that are related. Students are encouraged to utilize a variety of sources to provide a variety of perspectives on the answer or solution to the question at hand. These discussions are high energy, personal. critical, political, and sometimes even emotional. And we, as educators, need to make sure that all of the pieces are in place so that the conversation can happen organically and without your constant intervention.

Let’s be clear on goals

If I had to make a master list of what I’m aiming for my class discussion to be able to do, it would look something like this:

How to listen to and trace the development of claims and arguments

Building confidence in students owning their own voices

Practice synthesizing information

Build connections between ideas and elevate them to a new layer of the conversation

To learn the difference between neutrality and open-mindedness

To engage in discourse to deepen thought; not to be right or wrong

In order to accomplish these goals, it requires us, the instructors, to set up purposeful scaffolds on the front and back end of each discussion; however, in order for students to engage with the practice needed to meet these goals, we have to let the discussion happen organically and without our interference.

When to Stay Quiet

The simple answer? As much as possible. Your goal is to fade into the background during the discussion and closely observe student interactions and listen to the evolution of the conversation as it unravels organically.

Troubleshooting in the Background

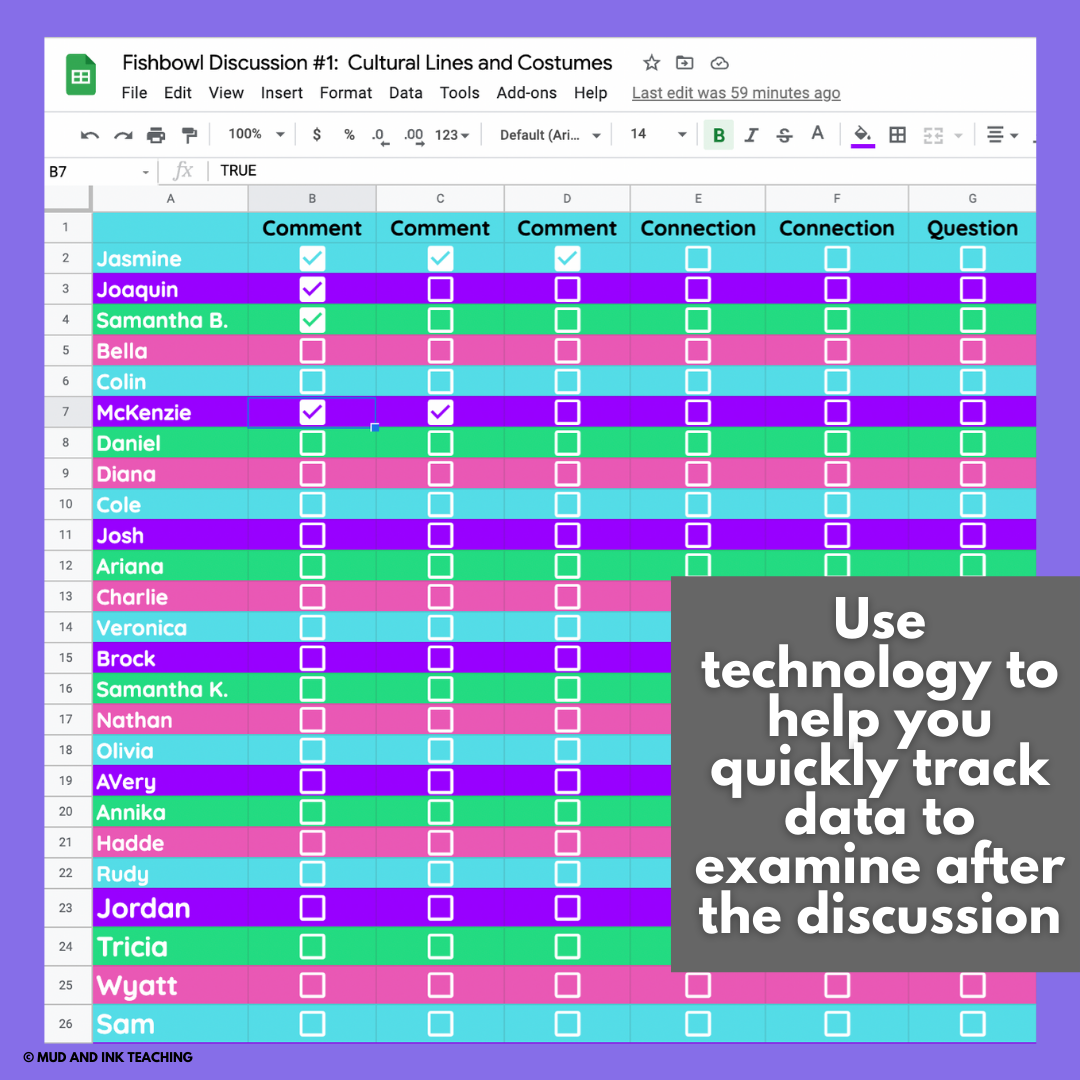

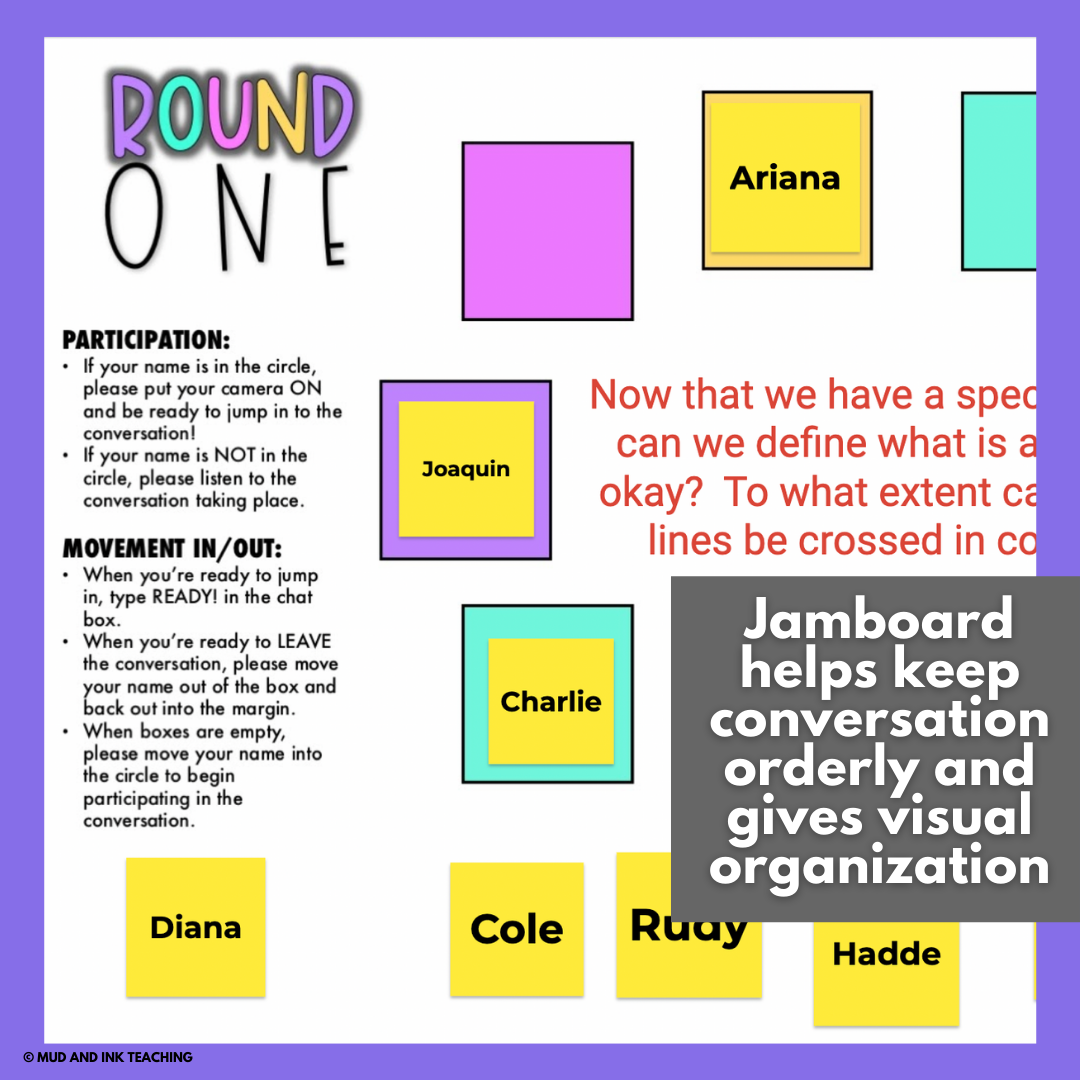

The logistics of these discussion strategies can be difficult to navigate the first few times though, so I’ve built two helpful tools that help me keep track of the discussion quickly and efficiently so I can spend more time paying attention to the content of the conversation.

Google Sheets Checkbox Tracker

Open up a new Google Sheet. Copy and paste your roster in the first column. In each additional column, use INSERT > CHECKBOX to create a clickable checkbox. You can label the columns “Comment 1”, “Comment 2”, “Asked a question”, “Used evidence”, etc. This is a simple way to track student participation without having to shuffle papers around. This task can also be assigned to a student if you are looking for ways for students to participate when they’re on an off-day. If students have access to a view-only version, they can monitor their own progress without you having to verbally remind students to speak up.

Google Jamboard

Jamboard is a unique tool that can help students keep track of who is in the circle and outside of the circle for a Fishbowl or Socratic. Using my Google Jambord templates, insert the template as the background image. Create a sticky note for each student with their first name. Give students “view only” access if you want to control the movement of students, or, leave it editable so students can move themselves inside and outside the circle. This works well for a virtual discussion or in classrooms where physically moving the desks into circles is particularly difficult.

Parlay Ideas

Parlay is an all-in-one tool that does the work of both the Google Sheets tracker and Google Jamboard. Parlay, when used for a live discussion, give students self-sufficiency and order as they navigate their difficult decisions. Whether you’re having a live discussion or a virtual one, Parlay will keep you away from logistical tasks and focused on the conversation at hand and will be delivered a data breakdown at the end of the conversation. Here are some ways I’ve used it with A Raisin in the Sun:

When to Speak Up

As much as we want our students to be engaged in a fully student-led discussion, there are times where our intercession is necessary. If we’re practicing these discussions over time, we might be intervening a bit more in the first one or two discussions, and gradually moving out as the students become more confident over time. Here are the times when we need to speak up:

If harm is done

Intentionally or not, there are times when student comments may be unnecessarily harmful or hurtful. Address these moments swiftly and clearly. Depending on the conversation at hand, you might prepare yourself for what might come up and plan ahead for how you will handle inappropriate takes on the conversation.

Time reminders

In both my seminars and my fishbowl discussions, I like to give clear indicators in time allotment. This helps students make space for others who still need to participate, be self-aware about their own contributions, and have a sense of where they stand within the class period.

A clarification/definition is needed

Especially when difficult topics are on the table, you might hear students skirting an argument. When my students discuss “To what extent can cultural lines be crossed in costume?” I can hear them nervously trying to not offend anyone by using generalizations. After listening for a while, I stepped in, offering a definition of “cultural appropriation” and asked them to use that definition moving forward to make delineations in their arguments. The definition helped provide clarity to the issues on the table and helped students have the language they needed to make their claims more solid.

Evidence reminders

Finally, I have found it both helpful and necessary to intervene in conversations that get too far away from the texts on the table. The generalizations mentioned above can mushroom, and sometimes I need to speak up with a quick, “Can we bring this idea back to the evidence?” or “Are there specific examples of this from something we read?” is enough to steer them back on track.

In Pursuit of Inquiry

No matter where you are in your teaching journey, know that the pursuit of inquiry and inquiry-centered instruction is the best path you can be on. Getting students to think for themselves, ask their own questions, and thoughtfully engage in important conversations is just as important as sharing great works of literature with our students.

LET’S GO SHOPPING

7 LatinX Poets You Should Be Teaching Right Now

Poems and poets come from all over the world and deliver POWERFUL and NEEDED perspectives to our students in a short, compact manner. Poetry studies don’t take the time that novel studies do. Pairing our texts alongside poems that provide additional voice and contrast is a critical practice that all English teachers should be working to make a regular occurrence in the classroom.

All too often, we blame our inability to showcase a wider variety of authors and perspectives in the curriculum on the “system”: the budget only allows for outdated novels, the curriculum is mandated and I have no room for flexibility, etc. But here’s the beauty of poetry: poems and poets come from all over the world and deliver POWERFUL and NEEDED perspectives to our students in a short, compact manner. Poetry studies don’t take the time that novel studies do. Pairing our texts alongside poems that provide additional voice and contrast is a critical practice that all English teachers should be working to make a regular occurrence in the classroom.

If you’re ready to do this work, I have seven poems here from LatinX poets that work beautifully within so many different kinds of units. Here are my favorites right now:

“One Day” by Richard Blanco

This poem works in any American Literature course (commentary on who we are / can be as a nation) and even treated as a piece of rhetoric and used for rhetorical analysis. The context of Obama’s inauguration is a powerful contributor to tone and impact on the audience, so jump on this piece for those skills!

“Afro-Latina” by Elizabeth Acevedo

Virtually every high school English department has a unit or even an entire course dedicated to themes or essential questions on identity. Here is the CORNERSTONE poem to use for this discussion. Acevedo delivers punchy lines and real-talk about her coming to terms with her mixed heritage: the combination of oppressed and oppressor. Students love this poem (and her books!) every time we watch it.

“Dear White Girls in My Spanish Class” by Ariana Brown

This poem offers beautiful commentary on the soul-searching parts of finding identity and the ways in which language is such an important part of this search. Perfect for a coming of age unit or any other story where teenagers are working out identity issues, this makes for a beautiful pairing.

“Invisible Workforce” by Bobby LeFabre

Bobby LeFabre’s metaphor game is strong, so if you’re looking to highlight that literary device, look no further. This poem is an ode to immigrant workers who mostly go unseen (the invisible workforce) and a celebration of their importance and a chance for them to be admired.

“Instructions on Not Giving Up” by Ada Limon

While there’s not a great video performance of “Instructions on Not Giving Up”, the poem on the page is accessible for students in a variety of contexts. The poem blends the imagery of nature and renewal with themes of resilience and perseverance.

“Abuelito Who” by Sandra Cisneros

Cisneros poetry is not widely available online for free, but this stunning poem about a grandfather is a one-click assignment with a free account on CommonLit. You can also find this poem in her collection My Wicked Ways” (affiliate link). This poem is about a grandfather aging and his inability to recognize himself in the process. The poem pairs nicely with stories that deal with multi-generational characters and, again, wrestling with identity as life stages continue to evolve and change who we always thought we were.

“I loved the world so much I married it” by Jose Olivarez

This poem is a beautiful and tricky poem (tricky in a fun, exciting way) that blends nicely into units exploring loss. Olivarez uses metaphors from nature and from familiar foods and recipes to connect his feelings of loss. Students will love how deeply personal the poem is and even have fun trying their hand at an imitation.

What are your other favorites? Who else would you add to my list? I’d love to hear in the comments!

If you’re working on giving students opportunities to write their own poetry, check out my free download to help students write slam poems that kick ass.

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

6 Ways to Highlight LatinX Culture in the ELA Classroom

Bring LatinX voices into your ELA classroom and curriculum all year long. Here are five easy places to start with a more diverse approach.

As we work as an educational community to bring stronger representation of our students to ELA curriculum, we must acknowledge the artistic, cultural, and linguistic works from the LatinX community. If you’re a busy teacher (I mean, aren’t we all!) finding the right artists, authors, and inspiration to find new ways to highlight the LatinX community throughout the year, I’m here with five ideas that will make your life easier and your curriculum even richer.

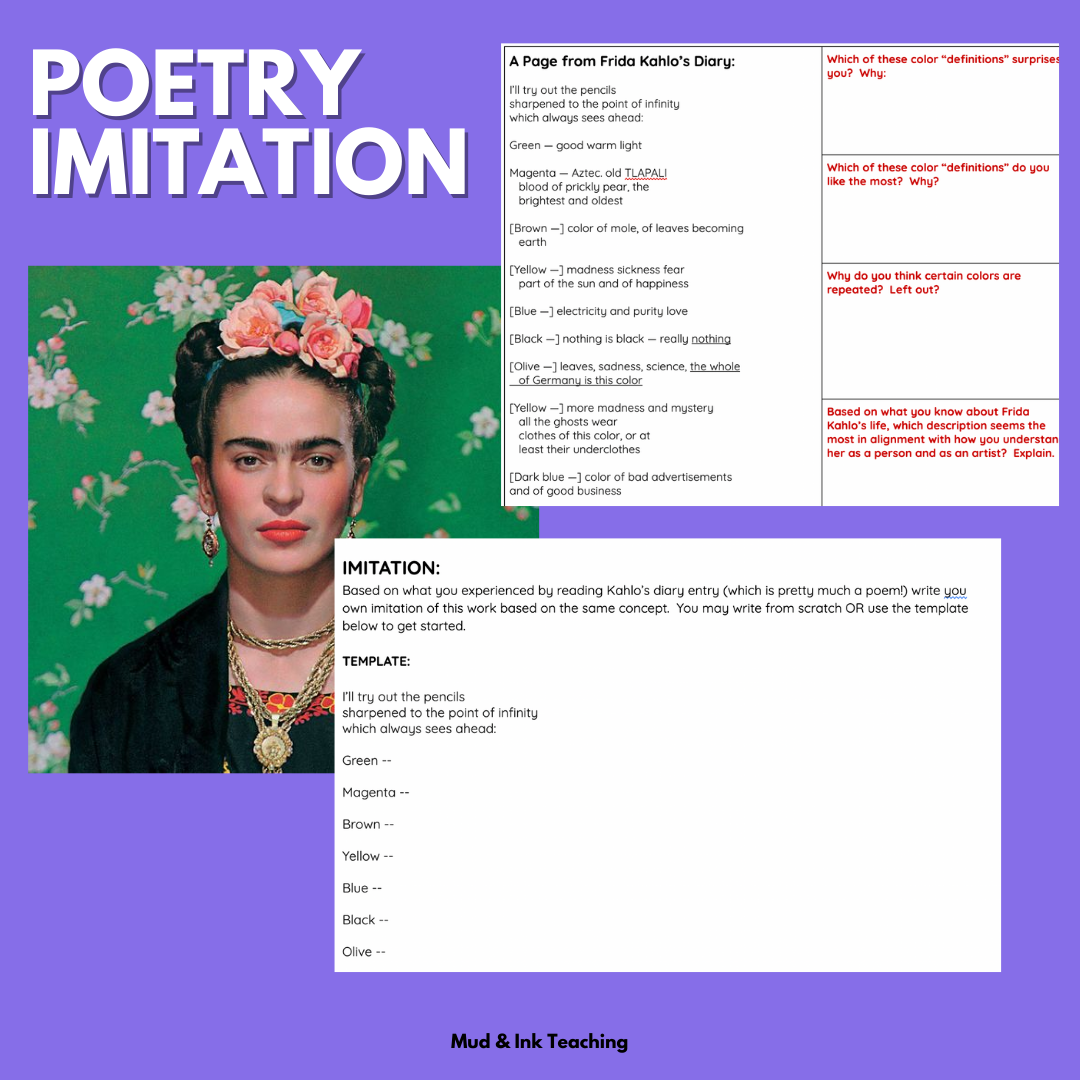

1. Close Reading New Voices

Small, bite-sized pieces of text and close reading is one of the easiest ways to streamline skills and layer in new voices to curriculum. I like to use my close reading templates paired with new, powerful texts and use them alongside other texts to make surprising connections. I’d love to share my Latinx author and creator series with you here featuring: Frida Kahlo, America Ferrera, Justice Sotomayor, Luis Alberto Urrea, and Richard Blanco. Each of these voices shares a unique LatinX experience with students and offers different opportunities for students to explore memoir, poetry, Hollywood screenwriting, and more!

Join the 5-week email series here!

2. Naming, Culture, and Language

As cultures and language continue to evolve and blend across the world, the feminine and masculine endings of Spanish words have taken heat as the world seeks to create more gender-neutral ways of referring to groups of people. Among these has been the uses of “Hispanic”, “Latino/a”, “LatinX” and, newly, “Latine”. As our work in ELA is the study of the English language, it’s fascinating to also look at other languages in contrast. Check out this Code Switch (occasionally explicit) episode about these terms and how they impact identity. For a quicker look, here’s a great article to check out. Even if this exact conversation doesn’t find its way into your classroom, this is worth our own study as educators as we seek to build our awareness of the communities we serve.

3. Elizabeth Acevedo “Afro-Latina”

In this highly energetic and passionate reflection on identity, Elizabeth Acevedo will stun your students in her poem “Afro-Latina”. In one line, she cries: “I know I come / from stolen gold. / From cocoa, / from sugarcane, / the children / of slaves / and slave masters. / A beautifully tragic mixture…”. Combine this piece with any unit or essential question exploring identity and you’ll have a seamless connection for students to analyze within the context of the unit you’re in. Have students pay attention to tone and imagery here especially.

4. Digital Choice Board

If it fits your calendar to celebrate the stories of LatinX voices for the whole month of Hispanic Heritage Month, this digital choice board will help you do just that. This simple board can be shared with students via Google Classroom (or other LMS), and they can choose from each of the five categories listed to dive deeper into stories, tradition, poetry, art, and books from fantastic LatinX authors and creators. Use this for bell work, for early finishers, or for added enrichment to any unit that you have lined up. Check it out here!

5. Decor & Representation

Over the summer and during back to school season, we’re very concerned about making our classrooms look appealing and feel welcoming. Our classroom decor, however, can be a powerful testament to helping students feel seen and communicating the authors, cultures, and stories that we value. To help you do that, I’ve designed some posters that can be easily printed, framed, and displayed any time during the year and give well-deserved shout-outs to some very big names in the LatinX author community.

6. SHOWCASE AUTHOR’S VOICE

When culturally diversifying curriculum, one important skill area to target is that of author’s voice. How does author’s voice emerge differently in one work vs another? How does one author speak about a topic in contrast to another? How does culture and language impact that tone? These questions and more are discussed in Brave New Teaching episode: Celebrating Diverse Voices: LatinX Writers (Episode 24). Listen in for some new ideas and grab the free download in the show notes for more close reading!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

How to Use a Makerspace in the ELA Classroom

If you aren’t familiar with a makerspace, it is a place where students can create, problem solve, and collaborate. One of the greatest benefits of implementing a makerspace is that it shakes things up from your normal routine. It gives your students the chance to get silly and creative while giving you the gift of seeing your kids in a totally different light. Not only does it foster learning through inquiry, but it also helps to build overall classroom community.

The Makerspace. A place for all the STEM teachers and students, right? WRONG! A Makerspace is something I couldn’t fully wrap my head around as an ELA teacher at the beginning, but after a few ideas (attempts and failures), I found a few things that helped me embrace the messy, hands-on possibilities for my ELA classroom.

If you’re more of an auditory learner (or you just don’t have time to read because you’re on your way to school!), you can listen to my ideas on the Brave New Teaching podcast on Episode 64. Find us on iTunes or right here to listen to the full episode!

If you have a bit more time to read, then here’s the slightly longer version…

As the great Ms. Frizzle says, take chances, make mistakes, GET MESSY!

The same rings true when using a makerspace in your classroom. You name it, it’s possible in a makerspace.

If you aren’t familiar with a makerspace, it is a place where students can create, problem solve, and collaborate. One of the greatest benefits of implementing a makerspace is that it shakes things up from your normal routine. It gives your students the chance to get silly and creative while giving you the gift of seeing your kids in a totally different light. Not only does it foster learning through inquiry, but it also helps to build overall classroom community.

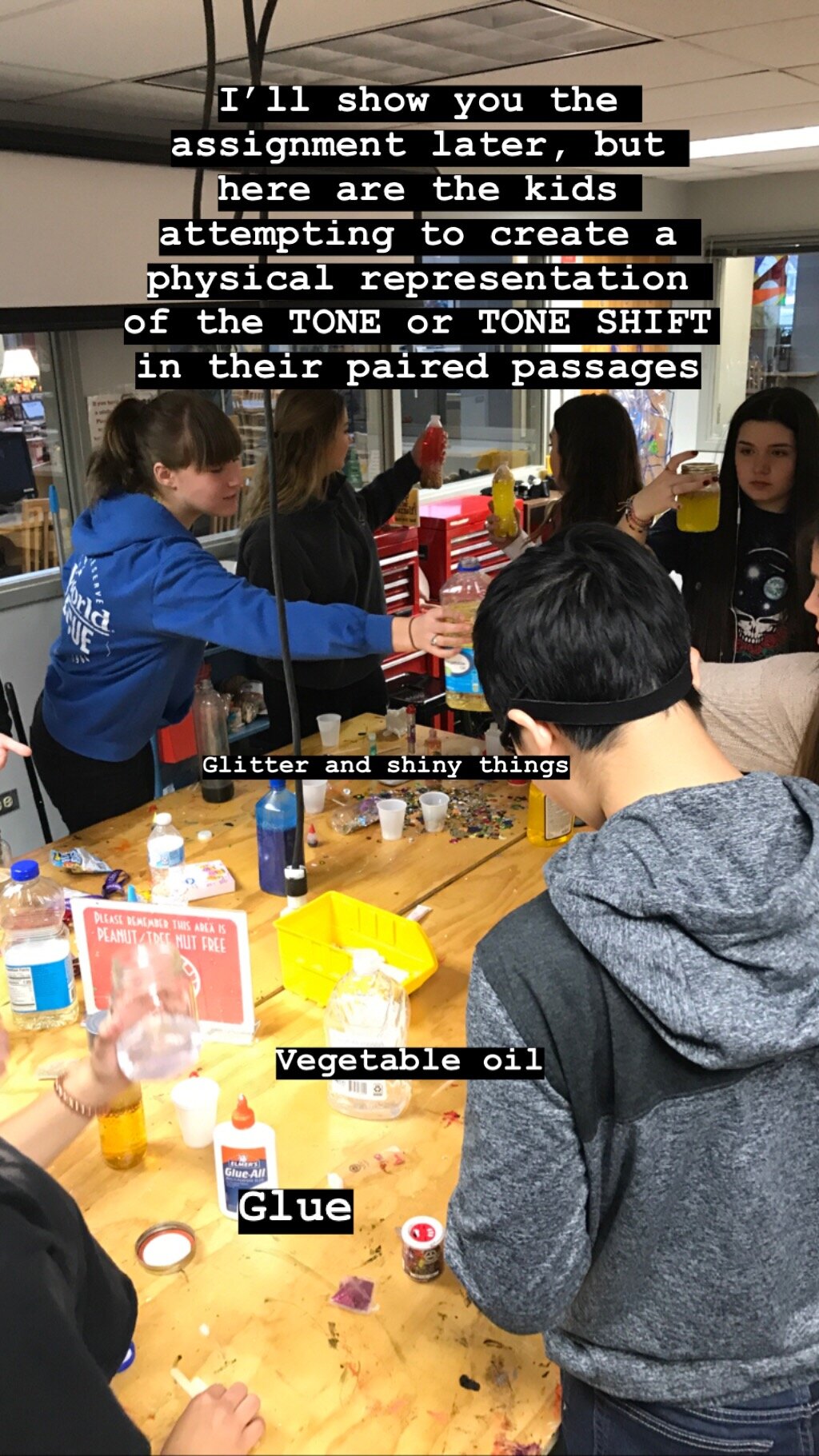

One of my favorite projects that I’ve done with my students was creating tone bottles to help them analyze the tone shifts in pre-selected passages from The Great Gatsby. The project itself is a bit silly, but the results were powerful in watching my students become more careful and close readers than they ever were before.

THE SPACE

Your makerspace doesn’t have to be organized in a meticulous or beautiful way. It should be full of odds and ends, most of which you probably have lying around your house. No matter what you include, your kids will find a way to use it! Consider:

Making your space mobile and shared. Find an abandoned cart and team up with a few other teachers to fill it with bits and bobs and slowly grow your supply stash over time.

This 3-tier rolling cart is awesome — I used it for a classroom library at school and now it’s a Makerspace cart for my toddlers at home!

Consider purchasing a green screen for anytime you want students to create something to film (reenacting a scene, a parody of a character, etc.)

Fabric scraps

Scrapbooking paper

Scissors

Hot glue and glue sticks

Things with glitter. And maybe some actual glitter. That’s up to you.

THE PROJECTS

The makerspace project that students create doesn’t need to be immediately rigorous, challenging, or even totally purposeful. Lean into the fun, frivolous, and silly for the project itself. We have the (good) tendency to want to make sure every single part of our instruction lines up neatly with skills and standards, but trust me, if you let go of the reins a bit in the “making” portion of this assignment, you’ll get a beautiful bang out of the analysis and reflection portion of the assignment.

WHAT TO MAKE?

A renactment of a scene using Legos (or headless Barbies, finger puppets, old socks, whatever)

An old-school diorama

A shoe box themed and filled to answer a question

A recreation of an important element of setting

A recreation of a motif or symbol

HOW TO ANALYZE?

What did you select in the creation of _________?

Why/how do these items accurately reflect ________?

How does this scene/symbol/object further contribute to your understanding of our Essential Question?

Given the limited supplies you had, why did you make x, y, and z choices?

Did you create your project based on your own interpretation (lens) of the text or did you attempt to recreate the author’s intention? Why?

THE GATSBY TONE BOTTLE

Valerie A. Person’s blog post inspired me to give this a shot in my AP Lang classroom. With her ideas in mind, I decided to challenge my students to select a passage from chapters 4 & 5 of The Great Gatsby and create a tone bottle that reflected the shift in tone from the beginning of the passage to the end of the passage. I then ALSO asked them to find a poem that had a similar tone or tone shift so that we could explore them as a pair.

It’s important to note that although this is a “makerspace project”, something that will involve obscene amounts of baby oil and glitter, the project begins and ends with textual analysis of TONE. I’m not trying to trick my kids here, but the reality is, we’re spending more time than they realize on the analysis part. Even the messy, maker part of the process is dependent on their initial analysis — they won’t even know what to put into the bottles if they haven’t analyzed (and reread and checked in with me!) the passage in the first place.

I’m happy to share my interpretation of this idea with you all. Here are a few pictures of how the project went, the sample I wrote for students, and a form to complete that will allow me to send over everything I have!

How to Use Attendance Questions for SEL in the Secondary Classroom

Keeping the pulse of your students’ social-emotional well-being is a high priority, so let’s blend it into a daily routine: taking attendance.

It can feel extremely overwhelming to take on the responsibility of your students’ social-emotional well-being as a teacher, and because this is so important for both the short and long-term health of the relationships building in your classroom, we need to take on this work without feeling burned with another “to-do” item on our lists.

While whole-class meetings and check-ins are extremely helpful, there’s something profound about small, daily, individual interactions with students. Daily sounds like A LOT of work, there’s something else that we do daily that can make this a daily class routine rather than an add on: taking attendance!

I’ll be the first to admit that before I started doing attendance questions, I was forgetting to take attendance. ALL. THE. TIME.

HI. It’s me.

But once I put attendance together with the idea of an SEL check-in, I was much more motivated to do this chore. An SEL check-in give me the chance to roughly gauge the energy of the classroom and get a feel for how students are feeling before we jump blindly into our material for the day. There are two ways that I’ve enjoyed doing these attendance check ins and go back and forth between the formats all year long:

GOOGLE FORMS / THIS OR THAT

This option is extremely low maintenance and offers a streamlined use of technology: Google Forms! I created a Google Form for each day of the school year that asks the same few basic questions:

BASIC INFO:

-Today's Date

-Student name

-Class period

HOW YA DOIN?

-This or that? (a photo-based question)

-Here, feel free to leave me a note. How are you feeling? What's going on? What questions do you have about class? (open-ended)

-I'M NOT OKAY: I'm having a really difficult time...

This does not apply to me

I need to schedule a Zoom meeting with you

Can you please call?

I just need you to know today was rough. No need to talk about it, just wanted you to know.

Other...

And that’s it! I assigned these through Google Classroom so I always had a paper trail of my attendance records and I could also see at a glance (through the response charts on the Form) the emotional temperature of my class. I could also see if particular students were answering the same way across multiple days and potentially intervene or keep that student after class to chat. Students never had to explain their answers, but always had the option to share more info in the Form or send me an email. Here are a few examples of our “this or that” questions (my personal favorite!)

BELL RINGER 4-SQUARE SEL CHECK-IN

Another way I was able to do some SEL check-in time with students was by asking them a similar type of question with visual responses. I call this the 4-Square SEL Check In. At the center of the square is my question: How are you today? Today is like…. Where are you today? What does my brain feel like? Which color are you today? Students respond by choosing the image that best (metaphorically) describes their mood or emotional state. I used them almost exclusively for attendance (they simply responded A, B, C, or D when I called their names, but they also worked great as:

bell ringer writing prompts

connections to characters in novels

embedded within a Google Form

ice-breakers for small group activities

Let’s have some fun. Teacher friends, let me check-in on YOU today. In the comments below, respond to the prompt: Where are you today? You may respond with only a letter, or, if you’d like, a little elaboration on how things are going in your year so far. We’re here to listen! Who knows…maybe you’ll connect with another teacher here!

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

Student Names Matter: Digital Ways to Learn Names

Knowing your students begins with knowing their names. It begins with pronouncing them correctly. Prioritizing this part of the back-to-school phase is critical and this blog post offers some easy ways to use technology to learn names quickly and correctly.

To my absolute horror and embarrassment, I can still remember the last day of school from my third year of teaching. One of my students, Andrea, gave me a hug and said goodbye, but also mentioned, “You know, Miss Cordes, you were my favorite teacher. But I should have told you that my name is pronounced AHH-ndrea not AN-drea”. After apologizing profusely and shaking my head in disbelief, I couldn’t stop thinking about the fact that she’s probably not the only student whose name I got wrong — for the whole school year.

Teaching is a whirlwind of chaos and instantaneous decision-making. And what I’ve learned over my years is that the chaos doesn’t stop, but what we CAN control are the things that we decide are important - the things that we decide to be intentional about. Learning student names (correctly pronounced!) at the beginning of the year has become a top priority for me and something I’m not willing to ever push aside again. Names are identity, history, and culture. Knowing someone’s name and addressing them by that name is a foundation in respect and rapport. I am committed to honoring these things about my students, whether I’m teaching in a physical classroom or in a virtual one.